Artist Q&A: This Earthen Door

Now on view at the Brandywine through September 7, This Earthen Door is a cross-disciplinary, photo-based exhibition that explores the pure color found in plants and the symbolism of flowers in art and literature. Inspired by an herbarium created by renowned poet Emily Dickinson—who was known in her lifetime as an accomplished gardener and student of botany—and her deep connection to the natural world, artists Amanda Marchand and Leah Sobsey worked with pure pigment drawn directly from plants to create a vibrant series of anthotypes. This plant-based photographic process was invented during Dickinson’s era just as photography was being born. In the interview below with the artists, learn more about their process and what inspired them to create this body of work, including two site-specific commissions based on plant specimens from the Brandywine’s Preserves.

How did your collaboration come about, and what got you both interested in exploring Emily Dickinson’s work in this way?

We met during graduate studies in photography at the San Francisco Art Institute, and our friendship grew with mutual interests in ecology, experimental photography, archives, and bookmaking. We knew that we wanted to collaborate on a project centering the natural world and feminism, and very quickly we decided to work with Emily Dickinson’s herbarium—a book of pressed plants the poet made as a teenager. Emily’s book of flowers was an object we had both come to know at different points and both secretly coveted. It had, one way or another, moved and inspired us. Dickinson’s herbarium lives in a temperature-controlled vault at the Houghton Library at Harvard University, and crumbles if handled, so it is off-limits to even the most accomplished scientists. We wanted to see or hold this special object—a forgotten treasure at the intersection of art and science—and knew we never could. As creatives we decided, why not make it for ourselves—and the world?

How did you go about creating the prints in the exhibition?

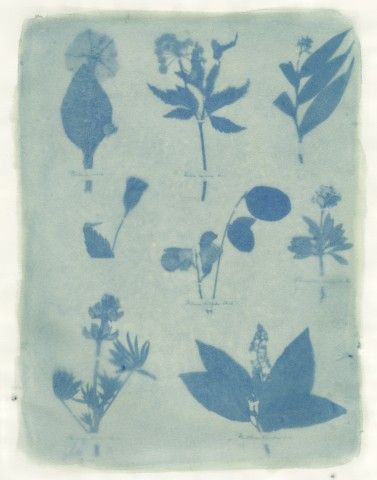

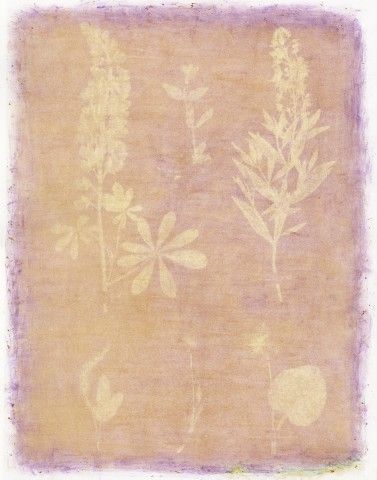

This Earthen Door reanimates Dickinson’s herbarium with an early-photographic plant-based process, known as an anthotype. After taking online classes to learn about the process, we selected different species of plants from the 424 specimens in Dickinson’s herbarium, growing them in our own gardens in Canada and North Carolina. To make each print, we used a mortar and pestle, creating a flower/plant emulsion, coating it on paper through a wet “wash” tincture or dry “rubbing.” This alternate rubbing preparation gave us, ultimately, two different colors per plant. We then exposed the coated papers to UV sunlight. Anthotypes are slow, taking days to months to expose properly. While it may look like we picked and laid actual living flowers down on paper, we did not. Instead, we used large, black & white photographic negatives of Dickinson’s herbarium for each exposure on top of the coated paper—so that each page is a color facsimile of the original. Our process is a mix of old and new, combining early, exploratory, photographic alchemy with new digital technologies. Gradually, as we worked coating papers many times to build up color and exposing them to the sun over that first summer and fall—then winter—the project evolved.

What is the meaning behind the title "This Earthen Door" and the titles of the works in the exhibition?

What we have loved in this project, is how a word, a poem, a flower, even a color, is never one thing but many things branching out into a web of associations, ideas and stories, crossing geographies and time. Our aim was, first, to reanimate Dickinson’s book of flowers—as a book. And what is a book, if not a door? Our title, “This Earthen Door,” is taken from a Dickinson poem that alludes to her own garden of earthen delights—a door to mortality—and immortality.

Did you have any unexpected discoveries while researching or working on this project?

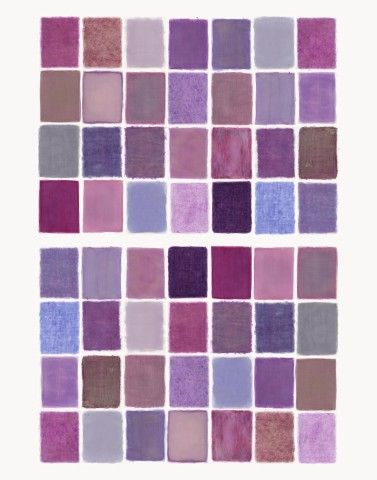

There were many rabbit holes and amazing discoveries along the way! We continued to fall in love with the incredible hues that each plant makes, especially with surprises like a pansy, which turned almost black-purple as a “rubbing” but when mixed with alcohol as a “wash” it became robin’s egg blue.

We also discovered how a geographical region makes an enormous difference in anthotype exposure time (as do fast summer exposures versus slow exposures at any other time of year). We were usually working in different locations—Leah in North Carolina and Amanda, for the bulk of the project, in Quebec—which influenced and produced different results. Leah’s exposures galloped along in the middle of her hot and humid southern summers; Amanda’s were slow during that first grey, chilly summer in Quebec.

What inspired your site-specific work at Brandywine’s Waterloo Mills Preserve?

Our site-specific pieces were inspired by the Brandywine Conservancy’s mission and environmental stewardship. Everyone is introduced to the stunning Museum grounds, but we were fascinated to learn of the two neighboring Brandywine sites, the incredibly bucolic Waterloo Mills and Laurels Preserve, which we visited several times with two of Brandywine’s Preserve staff members, Kevin Fryberger and Caleb Meredith. Their knowledge, guardianship, and conservation efforts, and those of the Museum and volunteers, inspired us to extend the working process of This Earthen Door, using native Brandywine species that cross over with Dickinson’s herbarium.

Talk not to me of Summer Trees speaks to the large tree repopulation efforts of both sites, but especially the Laurels Preserve, an area of almost 500 acres of hardwood forest that was badly hit by flooding a few years ago. The mission of tree restoration at the Brandywine is ongoing as climate chaos and habitat disruption continues. Large areas have been reforested with multiple tree species. Our piece incorporates 13 tree species found in Dickinson’s herbarium at both Waterloo Mills and the Laurels. Highlighting Brandywine efforts to keep native tree species thriving, this piece honors the Brandywine mission, history, and future.

Estranged from Beauty—None Can Be, our second commission, consists of a group of invasive species made as plant-based anthotype portraits. This piece points to an ongoing and long-term Brandywine eradication effort of invasive-introduced species, which outcompete native flora. Like our tree piece, each of these plants was collected at Waterloo Mills and can be found in Dickinson’s herbarium.