Since 2020, Brandywine has acquired 24 works by the Philadelphia born artist and educator Allan Randall Freelon. This exhibition endeavors to introduce audiences to Freelon’s life and work with a spotlight on these recent acquisitions.

Born in 1895 to a middle-class family, Freelon received almost all of his artistic education in the city where he grew up and worked his entire life. He attended many of Philadelphia’s leading educational institutions including the Pennsylvania Museum and School of Industrial Art (now the University of the Arts, 1912-1916), Philadelphia School of Pedagogy (now University of Pennsylvania, 1919), University of Pennsylvania (bachelor’s degree, 1924), the Barnes Foundation (1927-1929), and Tyler School of Art of Temple University (master’s degree, 1943). He also studied privately with Earl Horter and Dox Thrash, two of Philadelphia’s best-known printmakers. In 1921, Freelon was the first African American member of the Print Club of Philadelphia. He taught lithography at the Philadelphia Museum of Art from 1940-1946.

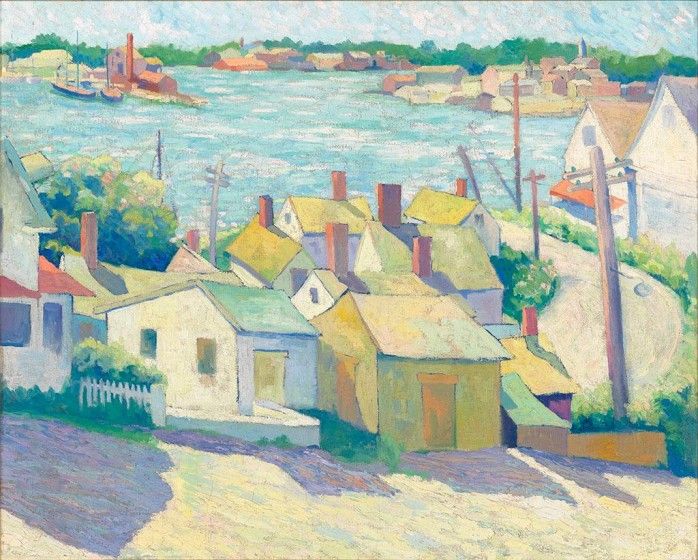

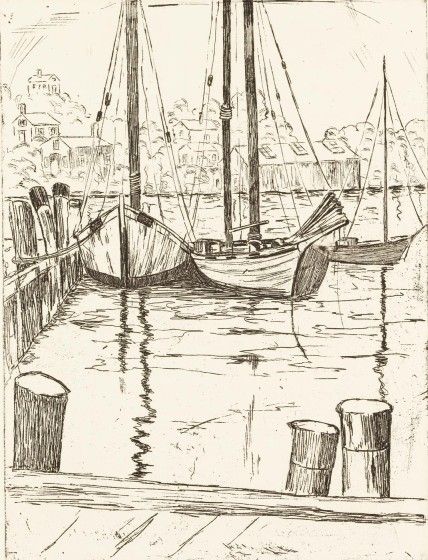

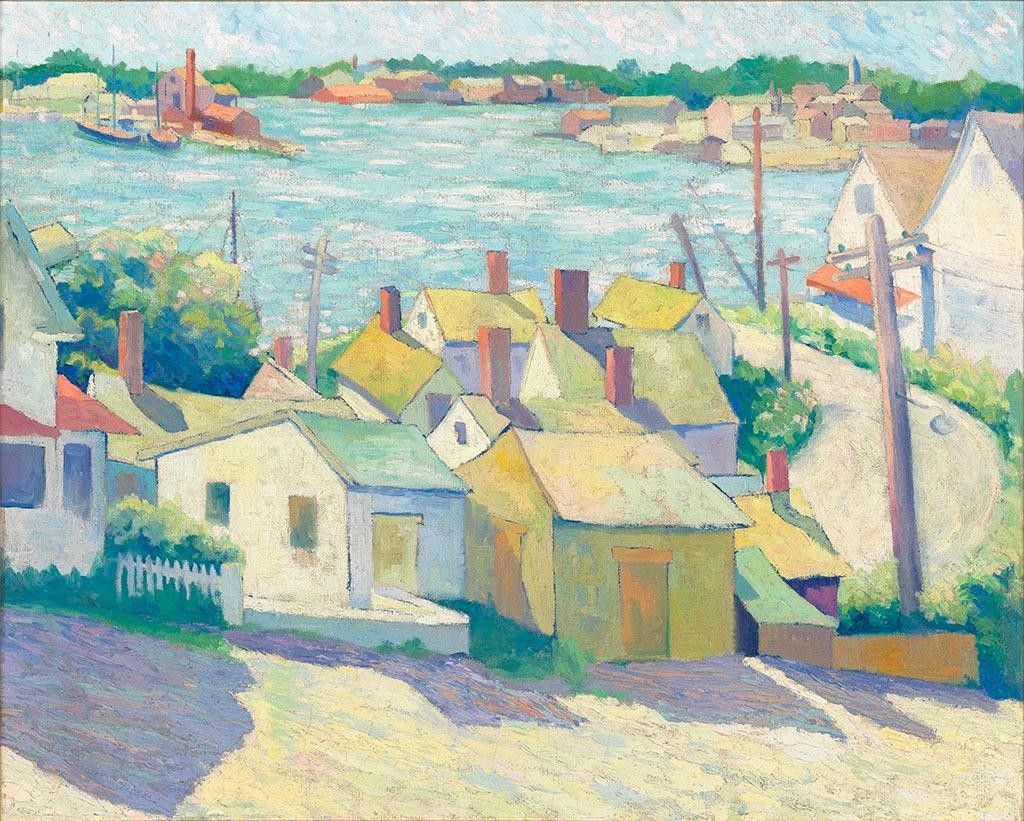

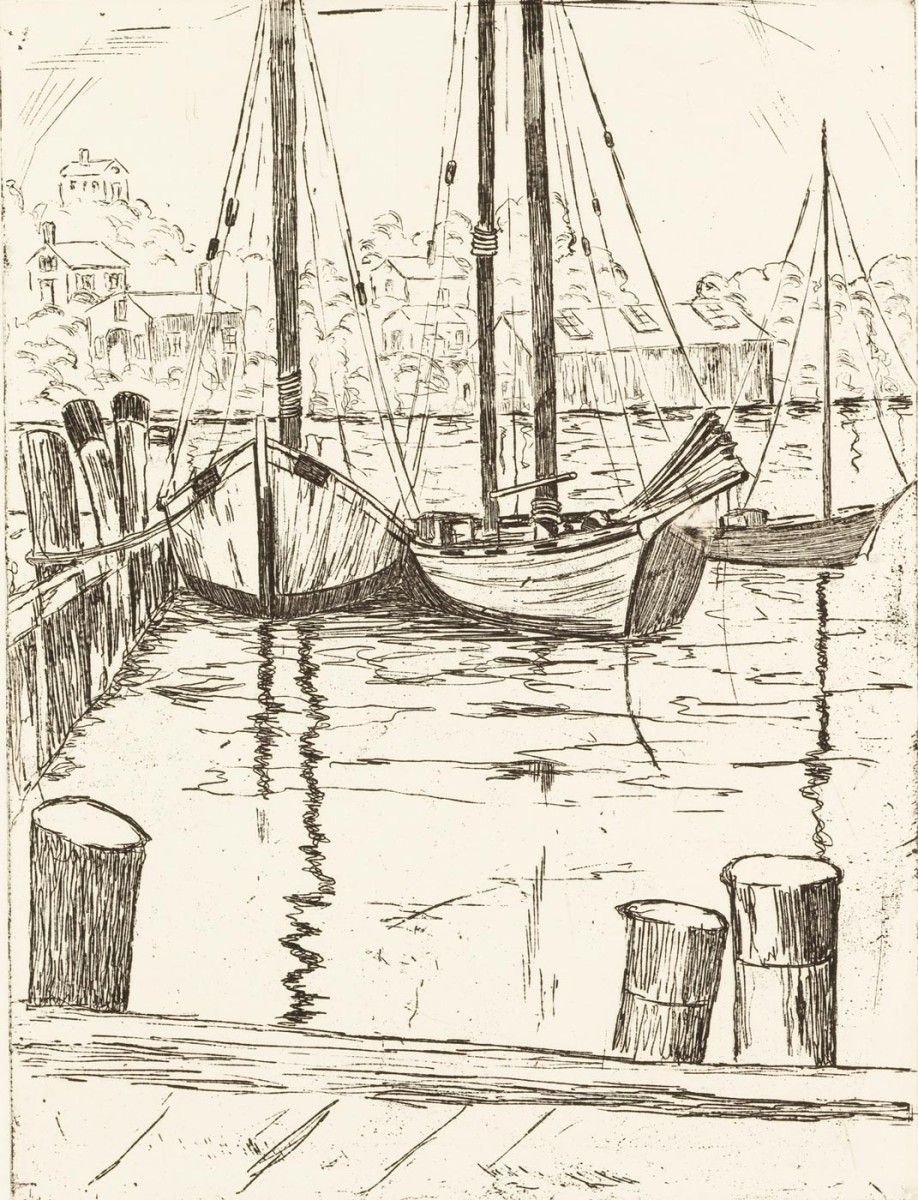

Freelon was a U.S. Army veteran of World War I, serving as Second Lieutenant. After the War he taught art in the Philadelphia public school system, where he was soon appointed assistant director of art education for the entire city, the first African American to hold the position. Over summer breaks from school, he traveled to Gloucester, Massachusetts, an established summer residence of a number of artists. His scenes of Gloucester harbor display the influence of Hugh Breckenridge, a teacher at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, who also summered there.

In 1921, Freelon exhibited at the Harlem branch of the New York Public Library, later known as the Schomberg Center for Research in Black Culture. He was also a regular exhibitor with the Harmon Foundation in New York, which promoted the work of African American artists through fellowships and exhibitions, including those that traveled across the country. He was active in Philadelphia exhibitions, including those at the Pyramid Club, an organization founded in 1928 by Black leaders in the city.

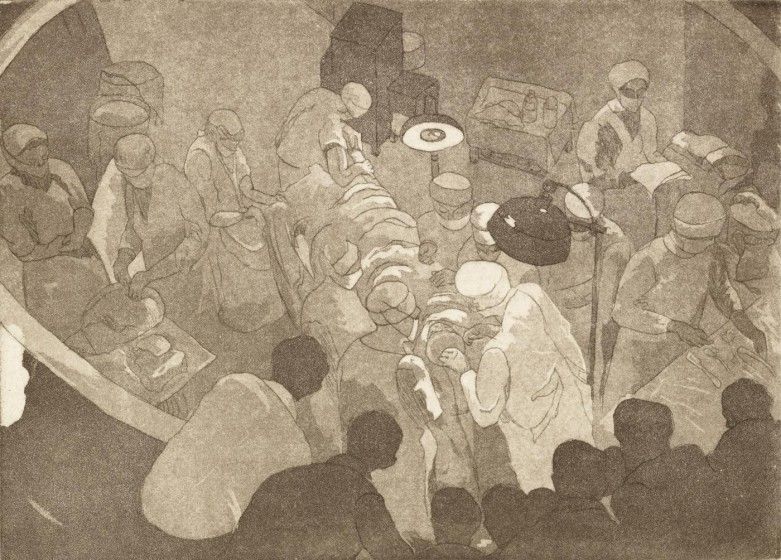

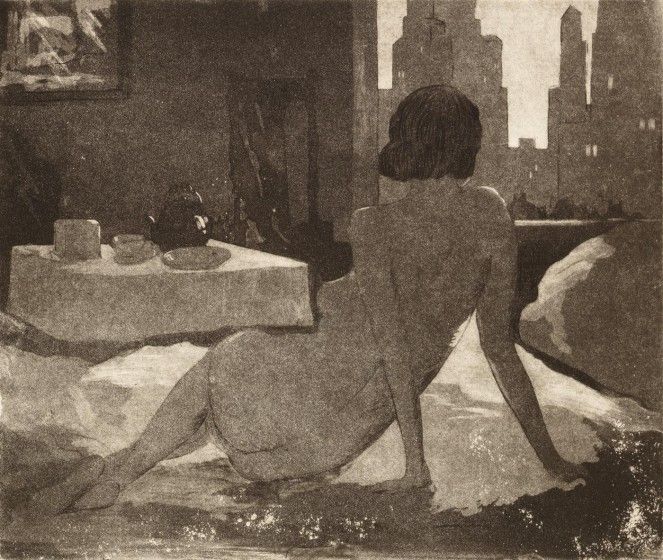

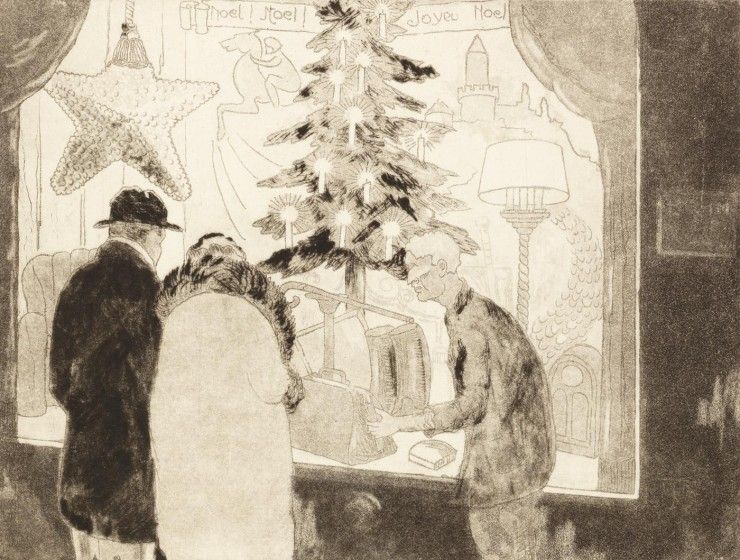

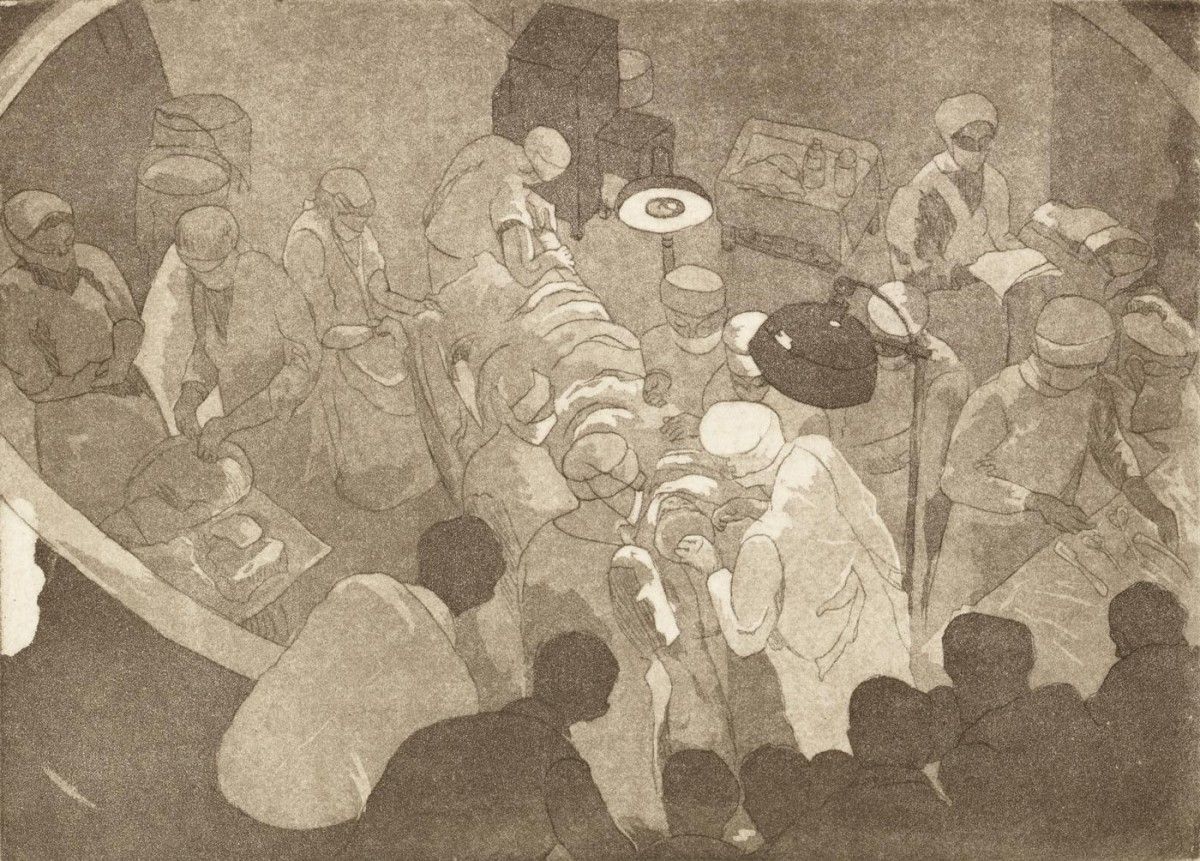

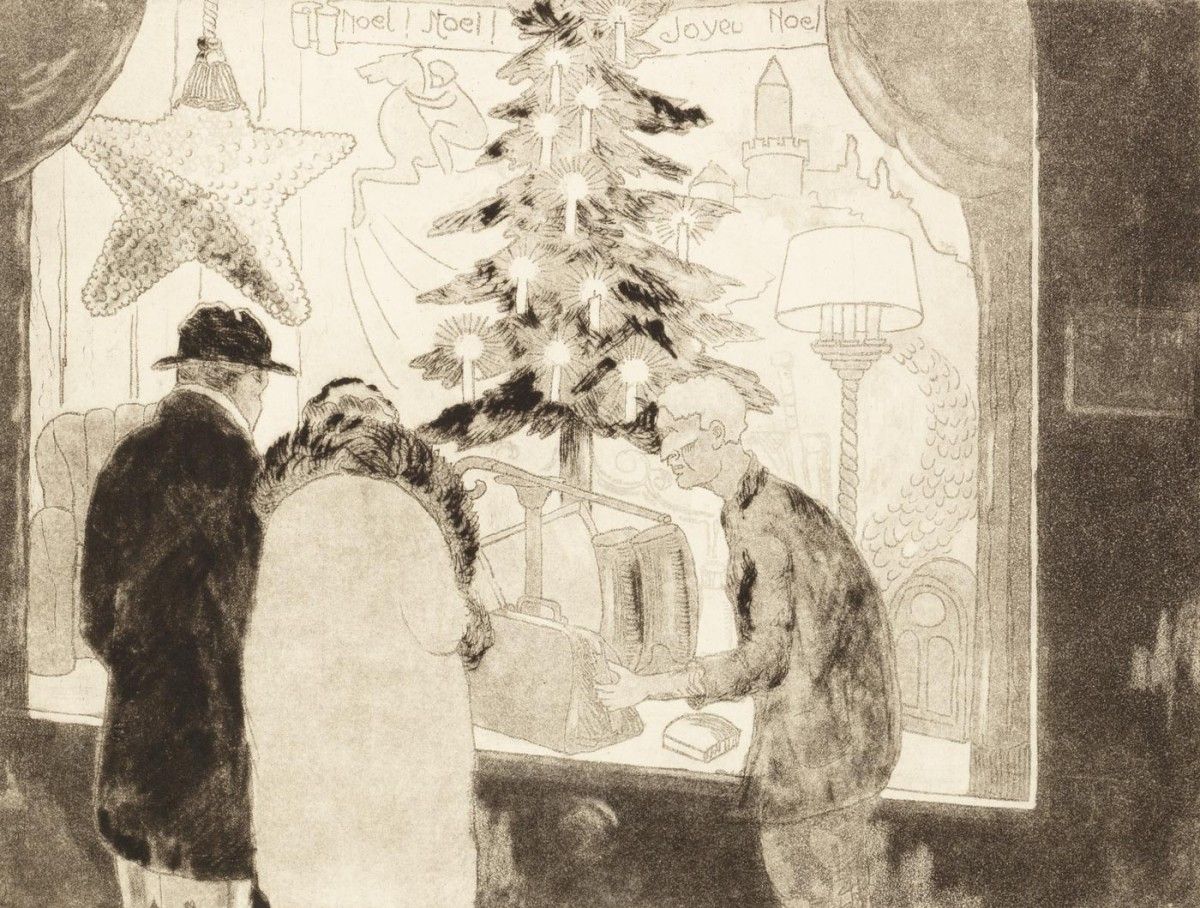

Though he worked during the Harlem Renaissance and knew many of the leaders of the New Negro movement, Freelon reserved his commentary on African American life for his print work, which tended toward the social realism of the 1930s and 1940s. His painted landscapes were in the vein of the popular American Impressionist artists, whose reach extended well into the twentieth century. According to the 2004 retrospective of his work at North Carolina Central University’s Art Museum, “Freelon believed Black artists, like their white contemporaries, should follow an independent and self-realized course,” without being beholden to proscribed subjects. In 1935, Freelon wrote, “While it is true that new talents were discovered and encouraged, it is equally true that this so-called ‘Renaissance’ and the emergence of what Dr. [Alain] Locke called ‘The New Negro’ offered a field day for writers of both races to advance their pet theories as to what the Negro should paint or sculpt.”

Freelon lived on a Montgomery County farm near Telford, Pennsylvania, called “Windy Crest,” where he bult a studio from which he worked and taught a racially diverse group of students. Many of Freelon’s paintings are still held by his family. His grandson, Philip Freelon, who died in 2019, was a celebrated architect responsible for the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture, the National Center for Civil and Human Rights in Atlanta, the Museum of the African Diaspora in San Francisco, and the Mississippi Civil Rights Museum in Jackson. He credited his grandfather for spurring his interest in the arts and design from a young age. His granddaughter Maya Freelon is a contemporary textile artist.