This exhibition examined how, after World War I, artists without formal training “crashed the gates” of major museums in the United States, diversifying the art world across lines of race, ethnicity, class, ability, and gender.

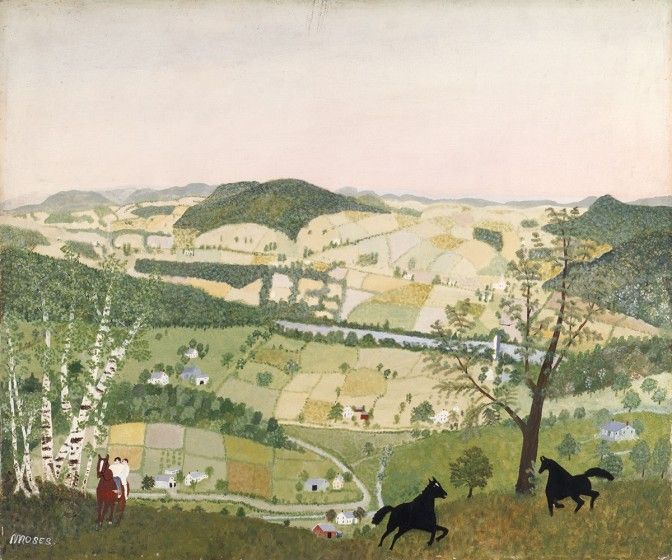

Included were over 50 works by celebrated painters such as Horace Pippin, Anna Mary Robertson “Grandma” Moses and John Kane, as well as by fifteen artists who are lesser known now but were recognized in their day, including Josephine Joy, Morris Hirshfield, Lawrence Lebduska, Patrick Sullivan, and others. The exhibition expands upon the High Museum of Art’s curator Katherine Jentleson’s book of the same title (University of California Press, 2020) and will reveal the degree to which the success of self-taught artists in this period was part of the mainstream art world’s ongoing search for “authentically” American art.

Gatecrashers was organized into thematic sections that explore the rise of the self-taught artist in this era:

American Mythologies explores how self-taught artists were celebrated as evidence of a creative excellence that was uniquely American. By virtue of being untrained, these artists were seen as free from the traditions and innovations that had made European artists dominant for centuries. The gatecrashing American artists rose from humble or marginalized beginnings and embraced national symbols in their work, making them more emblematic of core American values than their highly-trained counterparts.

Workers First examines how framing self-taught artists as workers became a powerful component of their popularity during the Depression era, when the idea of the multitasking, practical American had particular resonance. Whether it was John Kane’s labor in the steel furnaces of Pittsburgh, Anna Mary Robertson Moses’s time on the farm, Carlos Dyer’s work as a fisherman, or Morris Hirshfield’s rise through the ranks of Brooklyn’s textile factories, critics noted how these artists’ occupational histories (which were strongly associated with the subjects of their paintings) served as an alternative, nonacademic pipeline helping shape artistic excellence. Many self-taught artists, including Dyer and Josephine Joy, were at some point employed by the Federal Art Project, which underscored the association of art with labor, and thus worthy of the government’s work-relief programs.

Negotiating National Identity considers the factors that led to a spirit of multiculturalism in America in the 1930s and 40s: the legacy of the Harlem Renaissance and its continuation as the New Negro Movement, the Federal Art Project’s nondiscrimination policies, and advances in evolutionary science that debunked racial hierarchies and advanced cultural relativism. The success of Horace Pippin in this period—and the way in which he depicted race in his paintings, especially his work that depicts military themes—is one example of how self-taught artists became a diversifying presence in American art. Also achieving recognition were first-generation immigrants who came from countries and religious backgrounds that had been previously reviled by xenophobic Americans. In the years that followed, the category of self-taught art continued to be a place where ethnic and racial diversity succeed, revolutionizing who got to be called an American artist.

Convergence and Divergence with American Modernism explores the ways in which work by self-taught artists in this period both converged with and diverged from American Modernist movements. Alignments in style and subject matter led to exhibitions that integrated self-taught artists’ work with that of their trained peers, as in the Museum of Modern Art’s 1943 exhibition Realists and Magic Realists, which for example featured work by both the self-taught Patrick Sullivan and the highly-trained Ben Shahn. Gatecrashers will likewise display the work of self-taught artists Horace Pippin and Cleo Crawford alongside the academically-trained modernists Archibald Motley and Claude Clark. All four were Black artists who achieved recognition in the pluralistic atmosphere of the period. In the years that followed, however, the enthusiasm for Abstract Expressionism would largely rebuff both the diverse forms of modernism and representational approach that had characterized the interwar period.

The exhibition is organized by the High Museum of Art and curated by Katherine Jentleson, the High Museum of Art’s Curator of Folk and Self-Taught Art.

This project is supported in part by an award from the National Endowment for the Arts and The Dorothea and Leo Rabkin Foundation.

At Brandywine, Gatecrashers is sponsored by Chase.

Additional support is provided by the Matz Family Charitable Fund; Mr. and Mrs. Anson McC. Beard Jr.; and the Fawcett Family Foundation.