"Stuart Davis: Call and Response" is the first comprehensive exhibition focusing on the artist’s early formation between 1910 to 1940, from the time he left high school as a teenager to study with Robert Henri until his late 40s.

Expanding upon the legacy of Stuart Davis’s (1892-1964) love of jazz music, especially the 2016 retrospective, In Full Swing (National Gallery of Art and Whitney Museum of American Art), this exhibition explores how Davis’s early experiences with live jazz performances—when records were unavailable—shaped his pursuit of a vibrant new style of American modern painting.

The jazz technique of call and response in this exhibition serves as a framework for the chronological display of Davis’s early work and a metaphor for developing his own artistic voice. Much like a jazz musician responding to a melody, instrument, or voice, Davis engaged with a variety of creative stimuli—from his mentors to the cultural energy of New York and Paris—to craft his own unique artistic rhythm that would define the course of American modern art in the twentieth century.

A chronological selection of works from 1910 to 1940 reveals how Davis’s deep respect for jazz as the most authentic of any American art form shaped his artistic evolution. In his extensive archive of writings housed at Harvard University, Davis describes jazz musicians capable of transforming commonplace tin-pan alley tunes into masterful melodies. Davis himself spent a year in 1927-28 painting commonplace objects—a fan, rubber glove, and egg beater—in a series of Egg Beater paintings now widely considered early masterpieces of a distinctive American style of Cubism.

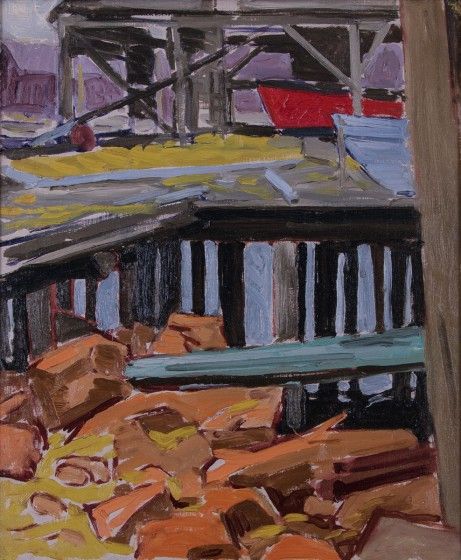

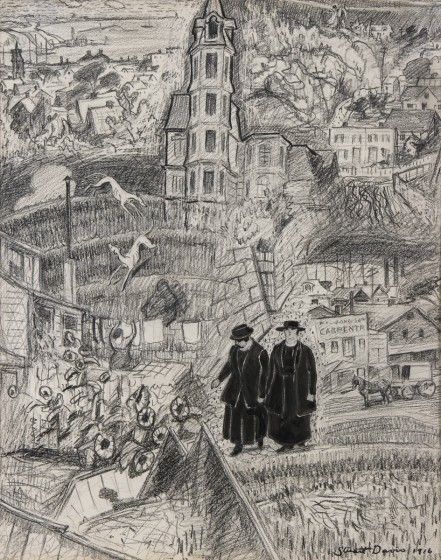

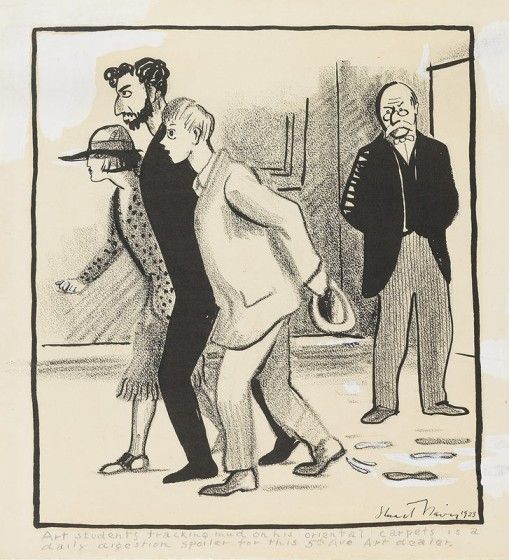

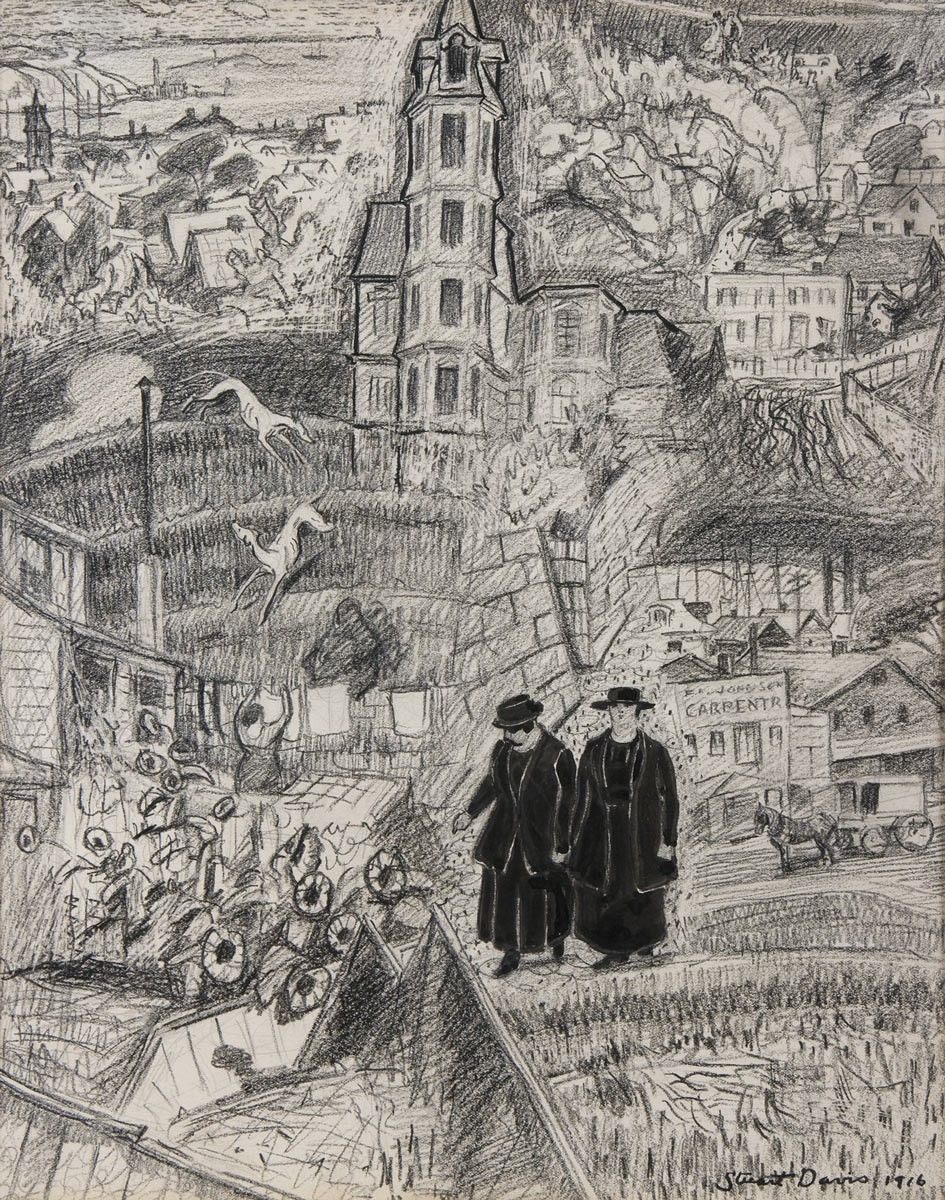

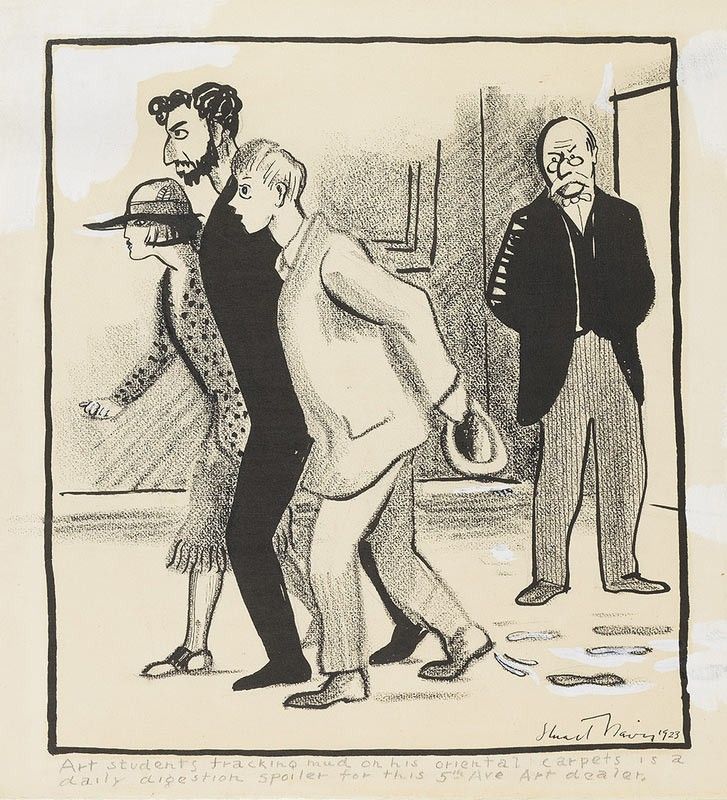

Guest curated by Elliot Bostwick Davis, Ph.D., the exhibition opens with Davis’s formal studies in New York City as a student of Robert Henri, who stressed the importance of experiencing modern life, and Henri’s colleague, John Sloan, who inspired Davis to contribute witty illustrations to The Masses, a progressive magazine Sloan edited. In 1915, Sloan encouraged Davis and his parents, both artists, to spend the first of many summers in Gloucester, Massachusetts. There, cluttered docks, tall-masted schooners, and cheek-by-jowl buildings became foundational elements of Davis’s early style. He often painted them inspired by the call of European painters he admired, especially Van Gogh, Matisse, and Gauguin, whose works he first experienced at New York City’s Armory Show of 1913.

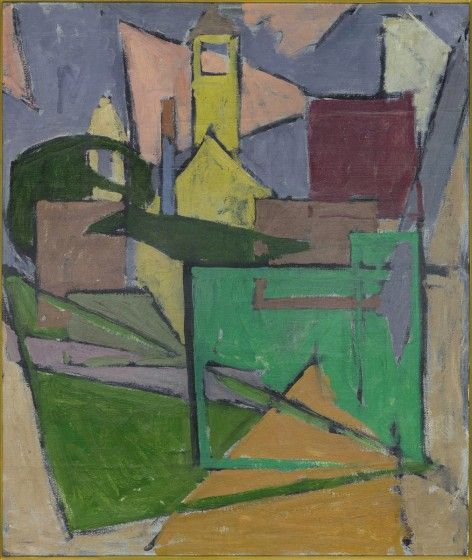

The exhibition then traces Davis’s exploration of Cubism during the 1920s, in New York City, Gloucester, and during his formative year as an expatriate in Paris. His responses—a synthesis of Cubist techniques with his uniquely American perspective—exude the improvisational spirit of jazz, with each new influence an opportunity for creative improvisation and reinvention.

In a section devoted to the 1930s, Davis’s works reflect deep engagement with social welfare for artists. Much like a jazz ensemble harmonizing distinctive instruments, voices, and audiences, Davis worked tirelessly founding and leading the American Artists Congress, while also supporting the Works Progress Administration by producing murals and prints as part of the relief effort.

The exhibition concludes in 1940, when Davis’s vibrant oil paintings and opaque gouache drawings synthesize many artistic calls he encountered over three decades into a dynamic visual response. By 1940, Davis exudes confidence, sophistication, optimism, and joy, showcasing his mastery of rhythm and improvisation akin to a jazz soloist at the height of their powers. Like a musician weaving together melodies and harmonies, Davis’s art pulsates with the nuanced interplay of emotions and ideas, presenting his multifaceted responses to the world. Together, these riffs on Davis’s early experiences in New York, Gloucester, and Paris, as described in his extensive writings, sketches, and paintings compose a dynamic symphony. Davis’s bold style, like a resonant jazz performance, became a clarion call for future generations. Artists from Jackson Pollock to Andy Warhol responded to Davis’s rhythm of innovation and iteration, each creating their own harmonic dissonances that would define American art during the second half of the twentieth century.

Stuart Davis: Call and Response is co-organized by Brandywine Museum of Art and Cape Ann Museum