New Lease on Life: Penguin Court’s Bluebird Trail

The Brandywine Conservancy's Penguin Court Preserve recently revitalized a 1.3 mile bluebird trail along its grounds, demonstrating the importance of predator guards and careful bird box placement. In the following guest article by D. Scott Jones, learn more about these recent changes, lessons learned, and the success that followed.

D. Scott Jones is a professional geologist, retired from a career with the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection, who participated in a Pennsylvania Master Naturalist training at Penguin Court in 2019. A lifelong, avid nature enthusiast and volunteer, he has contributed greatly to the Pennsylvania Master Naturalist program, Penguin Court projects, and many more organizations, even beyond state lines. It’s a pleasure to have him as part of our volunteer corps. As you'll read in the following article, his revitalization of the bluebird boxes at Penguin Court greatly improved the success rate of nesting and has enhanced the educational opportunities these structures provide.

Launching the Bluebird Trail at Penguin Court

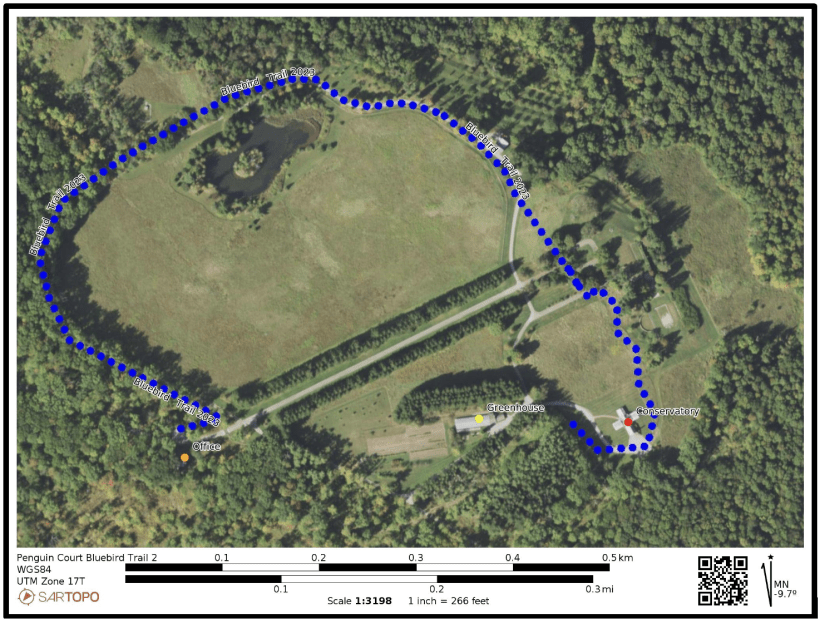

Penguin Court consists of approximately 923 wooded acres in Laughlintown, Westmoreland County, PA with about 50 acres of cleared fields and structures. Since the fields exhibited potential as prime nesting sites for the Eastern Bluebird (Sialia sialis), a 1.3 mile bluebird trail was established along the grounds at Penguin Court with help from with Ligonier Valley Middle School in 2019. “Bluebird trails” consist of a series of bluebird nest boxes placed along a walking path. The Ligonier Valley students constructed approximately 28 nest boxes for the trail—built using kits donated by the Pennsylvania Game Commission—and then positioned them in pairs on poles along the edge of the large field north of the Penguin Court greenhouse.

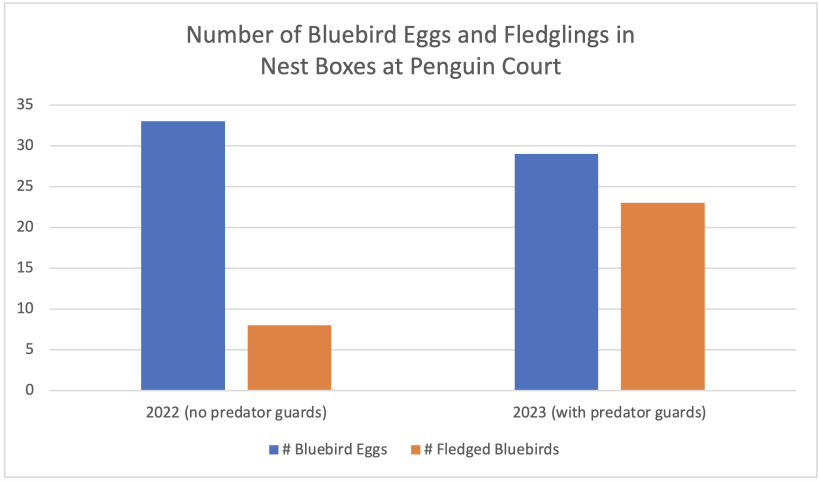

These boxes are monitored on a routine basis by volunteers, who collect data about the boxes’ inhabitants. In 2022, as a service project with the Westmoreland chapter of the Pennsylvania Master Naturalist (PAMN) program, PAMN volunteers worked to monitor and evaluate the bluebird trail. At the conclusion of the season, the monitoring program revealed approximately half of the boxes were not occupied. Ten of the occupied boxes produced eggs; however, only two nests were documented as producing eight bluebird fledglings. Tree swallows, house wrens, and chickadees were found in a number of boxes as well, producing at least eight fledglings.

Based off these findings, and drawing on my own personal experience from building and maintaining a 17-box bluebird trail for the last 26 years, I proposed to rehabilitate the boxes and trail at Penguin Court as a 2023 PAMN service project. In February 2023, Penguin Court’s Program Manager, Melissa Reckner, and I evaluated the bluebird trail, noting the areas that warranted improvement.

The major issues included:

- badly weathered boxes

- paired boxes on a single pole

- inadequate location (positioned too close to vegetation or on fence posts)

- the lack of predator guards

Rehabbing the Bluebird Trail

In the spring of 2023, work began on rehabbing the boxes and trail. Vegetation was cleared from around the poles, or the pole was relocated nearby to more suitable habitat. Weathered boxes that could be salvaged were repaired and painted. The paired boxes (two boxes placed back-to-back on one pole) were separated and put on individual poles roughly 10-20 feet apart, depending on the nature of the terrain. Several new boxes were installed, along with several donated Gilbertson boxes and ‘slot’ boxes.

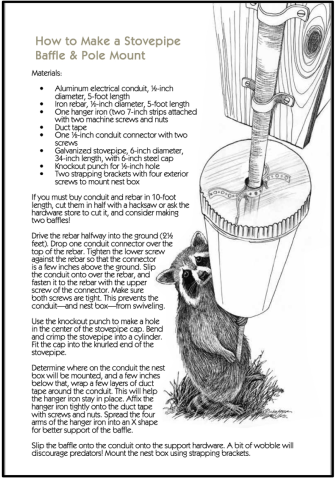

Along with the new/rehabbed boxes and poles, predator guards were installed on each of the poles. The two types employed were 6” metal stovepipe and 3” PVC pipe.

The green U-shaped poles provided a unique challenge in getting a proper fit for the hardware cloth around the pole. Instead of a metal cap, the baffles used at Penguin Court employed a section of metal hardware cloth bent so that it fit inside the stovepipe. Then, 1 to 2-inch vertical cuts were made in the top of the stovepipe and folded down onto the hardware cloth which was supported by the ‘hanger iron’ attached to the pole.

Because the baffles were not rigidly secured to the pole, they were able to sway slightly in the event a predator tried to climb up the pipe—the instability of the pipe serving as an additional deterrent to predators. Recent evidence also shows that the guard is best placed directly under the nest box which would normally prevent all but the largest snakes (6’+) from accessing the boxes. Moreover, the hardware cloth was used in an attempt to draw predators, such as snakes, up into the baffle (rather than along the exterior of the baffle) where their upward progress would be halted by the hardware cloth.

Results

Ultimately, 32 bluebird boxes were established along the 1.3 mile trail. Several PAMN volunteers continued to monitor the rehabbed boxes and proved the 2023 season much more successful, with 23 bluebirds babies fledging as well as 12 house wrens and three tree swallows.

During the 2022 nesting season, without predator guards, 24% of the bluebird eggs became fledglings, whereas in 2023, with predator guards, a whopping 79% of bluebird eggs became fledglings. This clearly demonstrates the importance of predator guards and careful box placement.

The rehabilitation of the trail will afford Penguin Court numerous public educational opportunities as well as providing PAMN volunteers additional avenues for future service projects. Thanks to Melissa Reckner and my fellow Naturalists for their help. It’s fulfilling to know birds will utilize these installed habitats.

Lead image: Ryan Hodnett, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons