Everything You Ever Needed to Know About the Freshwater Mussels of PA

Have you ever wondered what life is like for a mussel? With help from some local mussel experts, learn about the different species of freshwater mussels found in Pennsylvania, how they help keep water clean, and some of the environmental issues that are currently threatening their populations.

Pennsylvania is home to 50 different freshwater mussel species. Unfortunately, these aren’t the kind of mussels you’d ever want to eat. These mussels would taste like detritus and algae—basically the muck at the bottom of a pond. After all, that is what they eat all day! Mussels use a siphon effect with their gills to take in oxygen and filter out food from the water column. A mussel’s diet includes calcium carbonate, algae, bacteria, silt, detritus and other chemicals. Calcium carbonate is what many shelled creatures use to build their shells. Mussels use calcium carbonate for this same effect. Detritus is decaying organic matter that often takes the form of a smelly mud, which is rich in nutrients for any creature that braves eating it.

The mussels in our area tend to be the same size as those you would buy to eat. Some are larger, but anything smaller is likely an invasive species. If you’ve ever come across a mussel here in Pennsylvania, it was likely an Eastern Pondmussel or an Alewife Floater—the most common on this side of the state. Despite their hard shells, mussels have many predators, including waterfowl, river mammals like otters, and fish such as gobies. Mussels specialize according to the unique needs that their life cycle may call for. As an example, the salamander mussel will live in marshy areas where salamanders are abundant. Others live in ponds, streams, rivers and creeks, depending on where their symbiotic counterpart lives. This symbiosis is complicated, but it helps to first understand the life cycle of the mussel.

The Life of a Mussel

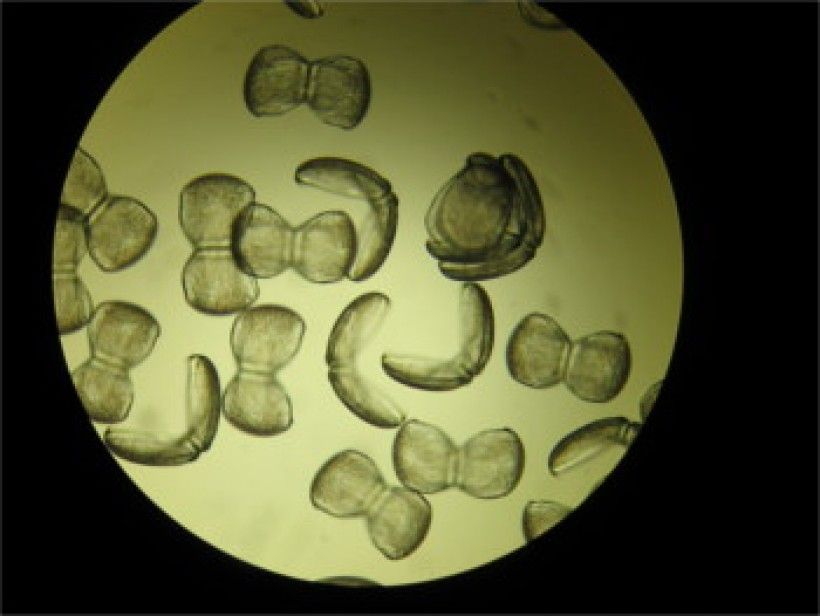

Mussels first start their lives as parasites, catching a free ride in the gills of a fish. The life cycle of mussels alone is simply fascinating. First, they are broadcast spawners—like coral. This means that the male mussels release their reproductive materials into the water, and the female catches these floating particles and use them to fertilize her eggs. After the eggs hatch into larvae (called glochidia), the mother mussel carries them in her mouth until a desirable fish host swims by. Different mussel species prefer different fish hosts, and researchers have found that they are very particular. One question that has continued to baffle the scientific community is how these sightless mussels know when the right fish host is about to pass—it’s a question that Fairmount Waterworks in Philadelphia is trying to learn more about right now.

As a fish host passes by, the mother mussel spits out her glochidia and sends them off to go live in the gills of the fish. The glochidia spend about a month of their lives in the gills, enjoying free nutrients. Once they grow too big, they pop off of the gills, float down to the bottom and burrow into the sediment—where they likely spend the rest of their lives. If they wanted to, they could use their foot-like appendage to roam around a bit, but these are relatively motionless creatures—too slow to evade predators by running away. If in motion, a mussel is likely trying to escape sinking water levels or search for a better place to sit and eat. They do so by placing their foot in the sediment, an inch or so in front of them, then dragging themselves forward.

Threats to Mussel Populations

Many local mussel populations have suffered the negative effects of industrialization. Over centuries, the waterways of the Piedmont in Pennsylvania and Delaware were rendered inhospitable to mussels. People built dams, spewed pollutants into the water, dredged our rivers, and severely damaged pristine ecosystems. This degradation of our waterways went on up to 1970s, until the passage of the federal Clean Water Act, Pennsylvania’s Clean Streams Law and the founding of many pro-environment organizations—developments that greatly reduced water pollution. Still, the dams remain and their devastating effects on the mussels continue. These dams prevent fish from moving about from place to place in the river as they normally would. Because of the lack of fish hosts in certain areas, many mussel populations are unable to complete their life cycle. This has led to a massive loss of mussels in affected areas. The Eastern Pondmussel is threatened and 10 other Pennsylvania mussel species have hit endangered status.

Combatting the Decline

Although humans have been able to make headway in tackling “point-source pollution,” or pollution that directly is dumped into water from a known source, we still struggle to manage “non-point-source pollution,” such as runoff—which is harder to address because it has so many sources. Mussels can have a huge impact on “non-point-source pollution” in our streams and waterways. They filter up to 15 gallons of water in a single day and they feed on tiny particles in the water column—making up an excellent clean-up team! Since they lack discretion, they can also consume a lot of our pollutants.

While population decline is threatening some of our local freshwater friends, there is still hope. Dams have been one of the main impacts on the decrease in mussel populations. By removing some of the most impactful dams, we can reconnect habitat for a number of species, including mussels. The City of Wilmington removed the first dam along the Brandywine in November of 2019. As a result, American Shad have returned upstream ½ mile and spawned there where they were once native. Such actions have been found to benefit Alewife Floaters, a mussel species in our area that is reliant on American Shad as fish hosts. The Brandywine Conservancy continues to play a crucial role in this process as part of Brandywine Shad 2020, focusing on efforts to remove dams in Pennsylvania. Brandywine Shad 2020 is a local organization that is working to either remove or modify the remaining dams to allow fish passage along the Brandywine in Delaware and Pennsylvania and further restore shad to our area. The Conservancy was one of its founding members.

The research team at Fairmount Water Works also has a plan to help reintroduce a number of freshwater mussel species that were once abundant in the Delaware River watershed. In five years or less, they hope to open a hatchery at Bartram’s Garden to help grow their population once more.

It’s important to note that only certain species of mussels are native to our area—others are not and can cause a lot of harm if they enter the wrong river. For example, zebra mussels, native to Eurasia, have become a growing issue in Pennsylvania. Because they use fish hosts, mussels can distribute themselves across large areas quite rapidly, which can be harmful in the wrong setting. Too many mussels can alter water chemistry and remove too much healthy plankton. Experts have started a detailed plan for research and reintroduction called the Mussels for Clean Water Initiative, which could eventually transform New Jersey, Delaware and Pennsylvania for humans and mussels alike. Stay tuned as we look forward to a future of river health where humans and mussels help each other out in our own kind of beautiful symbiosis!

Credits:

Special thanks to our mussel expert friends in Philadelphia, Bria Wimberly and Damian Ruffner at the Discovery Center, and Stacey Heffernan at Fairmount Water Works, for sharing their knowledge!