Vernal Pools and the Amphibians Who Love Them—Your New, Noisy Neighbors

Are you the kind of individual who likes to hibernate in cozy blankets on a comfortable sofa for the winter? Does a big mug with hot tea and a book, or a marathon session of your favorite TV series sound like the perfect thing for winter? Rest assured; you are not alone! Indeed, certain animals experience these same “hibernating” symptoms.

Brumation is a dormancy undergone by ectothermic (“cold-blooded”) species. It’s a biological reaction to the environment for animals unable to regulate their own body temperatures. They enter into a state of sluggishness, inactivity, or torpor (similar to the state us humans might enter while coach surfing during the long winter months). Amphibians, particularly, can conserve energy, have less need for food, and survive lower temperatures by slowing down their metabolic rate during brumation.

For us humans in March, the symptoms of seasonal affective disorder start to become more common as we long for the warmer and sunnier days of spring. It’s not all that different for the ectotherms. As the days begin to grow longer, activity levels of amphibians and reptiles increases. This response to seasonal changes in day length is called “photoperiodism.”

Brumating animals start to wake up when the day’s length increases and begin the mating process in vernal pools if the environmental and weather conditions are suitable. Vernal pools are small, seasonal depressions that temporarily fill with water. These pools typically fill in the fall or winter due to rain and snow fall and remain ponded through the spring. They will dry completely by the middle or end of summer each year. This seasonal drying prevents fish from establishing populations, which is critical to the success of species that rely on breeding habitats free of fish predators. These vernal pools are essential for the breeding success of several amphibians in our region.

Amphibians are highly sensitive to environmental changes because they live in both aquatic and terrestrial environments and breath through their skin. The diversity of amphibians you can find in vernal pools in the spring on your property is one of the best indicators of the environmental conditions and ecological health of your property. Since amphibians are so sensitive to changes in temperature and moisture, they can be helpful indicators of the negative effects of climate change on local ecosystems.

So forget that book or tv show! Grab your warm blanket and mug of tea and curl up to look at these amphibians found in our region in these seasonal woodland ponds. If you’re feeling the effects of photoperiodism, you can even venture out to find them on your own!

If you are interested in learning the amphibians and reptiles that you have on your property, check out this article and reach out to the folks at the PA Amphibians and Reptile Survey.

Wood Frogs (Lithobates sylvaticus)

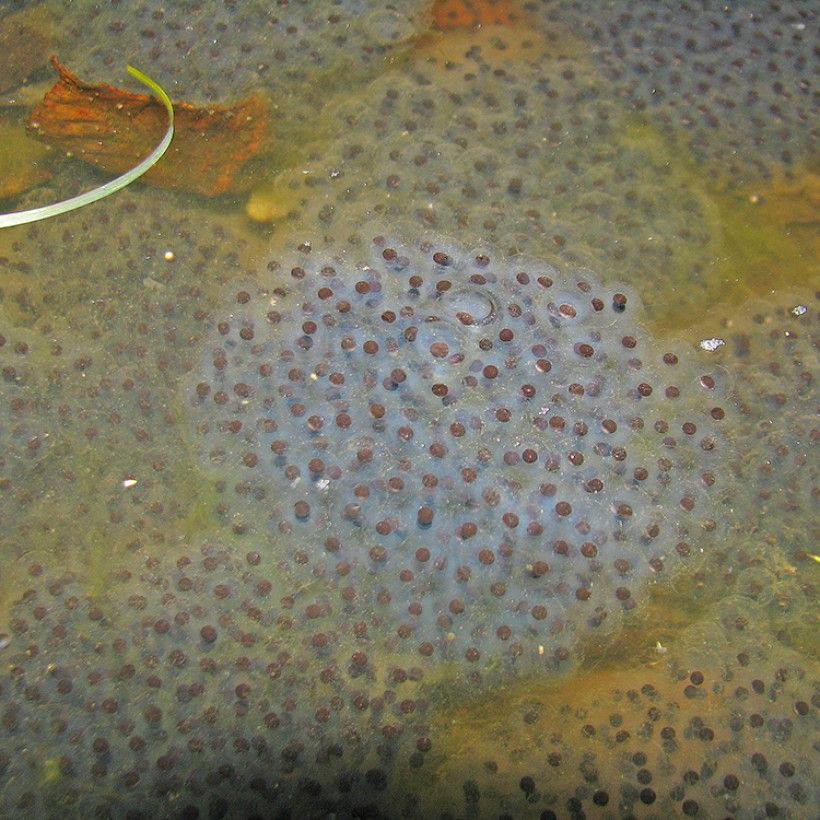

Wood frogs breed primarily in woodland vernal pools. They are one of the first frogs to begin the breeding season, usually in early March. Males can be heard at this time making their distinct quack-like calls day and night. Females lay 1,000 to 3,000 eggs, which hatch between nine and 30 days later.

Eastern American Toad (Anaxyrus americanus)

In the spring, American toads move from their winter terrestrial brumation sites to breeding sites within shallow, often grassy, areas in lakes, ponds, streams, vernal pools, prairie potholes, farm ponds, floodplain pools, ditches, or streamside pools. Their tadpoles require small, open, still water devoid of fishes. Males call in large choruses, usually beginning in early evening. They can also be heard in the daytime on particularly warm and humid days. Females lay between 4,000-15,000 eggs in two long strings, usually entwined around vegetation or resting on the pond bottom in shallow water. They begin migrating as early as late February, with peak breeding mid-March to mid-April.

Spring Peeper (Pseudacris crucifer)

Spring peepers spend their winters in soft mud near ponds, under logs, or in holes or loose bark in trees. Early in the spring you will begin to hear the male’s signature mating call—a high-pitched whistling or peeping sound repeated about 20 times a minute. They call on warm spring nights and during the day in rainy or cloudy weather. Females lay their eggs in vernal pools, ponds, and other wetlands where fish are not present. They lay anywhere from 750 to 1,200 eggs, which attach to submerged aquatic vegetation. Depending on the temperature, they can hatch within two days to two weeks.

Pickerel frog (Lithobates palustris)

The Pickerel frog breeds from late March to May in our region in vernal pools, stream overflow pools, farm ponds, sinkhole ponds, floodplain wetlands, marshes, and flooded quarries. During this time, you will hear the male’s low snore-like call.

Females lay between 700-3,000 eggs in spherical masses attached to dead or submerged vegetation at or near the water surface.

Red Spotted Newt (Notophthalmus viridescens)

The red spotted newt has four distinct life stages: egg, aquatic larvae, terrestrial adult (red eft) and aquatic adult (newt). During breeding migration, the efts come from their forested terrestrial sites into aquatic habitats. The breeding adult newts overwinter on land and migrate to the breeding aquatic habitats at the same time. Spring migration peaks in late March and is concentrated around rainy days and nights.

The red spotted newt uses both not permanent and semi-permanent bodies of water for breeding, including pools, ponds, wetlands, and low-flow areas of streams in forests. Females deposit their eggs singly, wrapping each in a folded leaf of submerged aquatic vegetation, in a decaying leaf, or in other detritus. Mature, overwintering adults deposit eggs earlier in the breeding season than do efts returning to the water to breed for the first time. Each female lays between 200-375 eggs over many weeks.

Marbled salamander (Ambystoma opacum)

Marbled salamanders reproduce on land, in or near their wetland breeding sites prior to pond filling. They begin their breeding migration in the fall on rainy nights. Breeding sites are generally the dried beds of temporary ponds, the margins of reduced ponds, or dry floodplain pools. Females construct nests and lay their eggs under cover where the nest is likely to be flooded by subsequent winter rains. Egg masses are spherical in shape. The female marbled salamander will typically stay at the nest protecting the eggs until the pool begins to fill with water from rainfall or snowmelt. Embryos develop to a hatching stage, but do not hatch until the nest is flooded. The larvae develop in the vernal pools for about four and a half months, when they leave as immature terrestrial adults.

Spotted Salamander (Ambystoma maculatum)

Spotted salamanders migrate to their breeding ponds in late winter and early spring when temperatures begin to warm up and rain showers arrive. They lay their eggs mid-March through mid-April. The females attach the egg masses to vegetation in the vernal pool or rest them on the bottom. Egg masses are clear to milky-white, often developing a greenish color over time due to algae. Embryos hatch mid-May to June and the larvae develop for a few months, transforming into immature terrestrial adults from August through September.

Four-toed salamander (Hemidactylium scutatum)

Four-toed salamanders are strongly associated with sphagnum moss and are found in forested areas that have bogs, marshes, or vernal pools. Breeding occurs on land in the fall and only the females migrate from April to mid-May to the banks of ponds, bogs, or streams to deposit their eggs. They nest in moss that overhangs or is near the edge of the water. Females sometimes lay eggs in a solitary nest and brood them. Other times, multiple females may deposit eggs into the same nest with only one female brooding. The eggs hatch and the larvae enter the water where they develop from 20 to 40 days.

Header image: Wood frog (lithobates sylvaticus). Photo by Kevin Fryberger.