Fritz Eichenberg & The Art of Printmaking

The German artist and illustrator Fritz Eichenberg was a master of many printmaking techniques that allowed him to take his intricate designs and multiply them manifold. Indeed, Eichenberg studied printmaking at the Academy of Graphic Arts in Leipzig and started work as an illustrator even as a young man, before fleeing Germany for the U.S. during World War II. He even wrote the book on printmaking, called The Art of the Print, Masterpieces, History, Techniques.

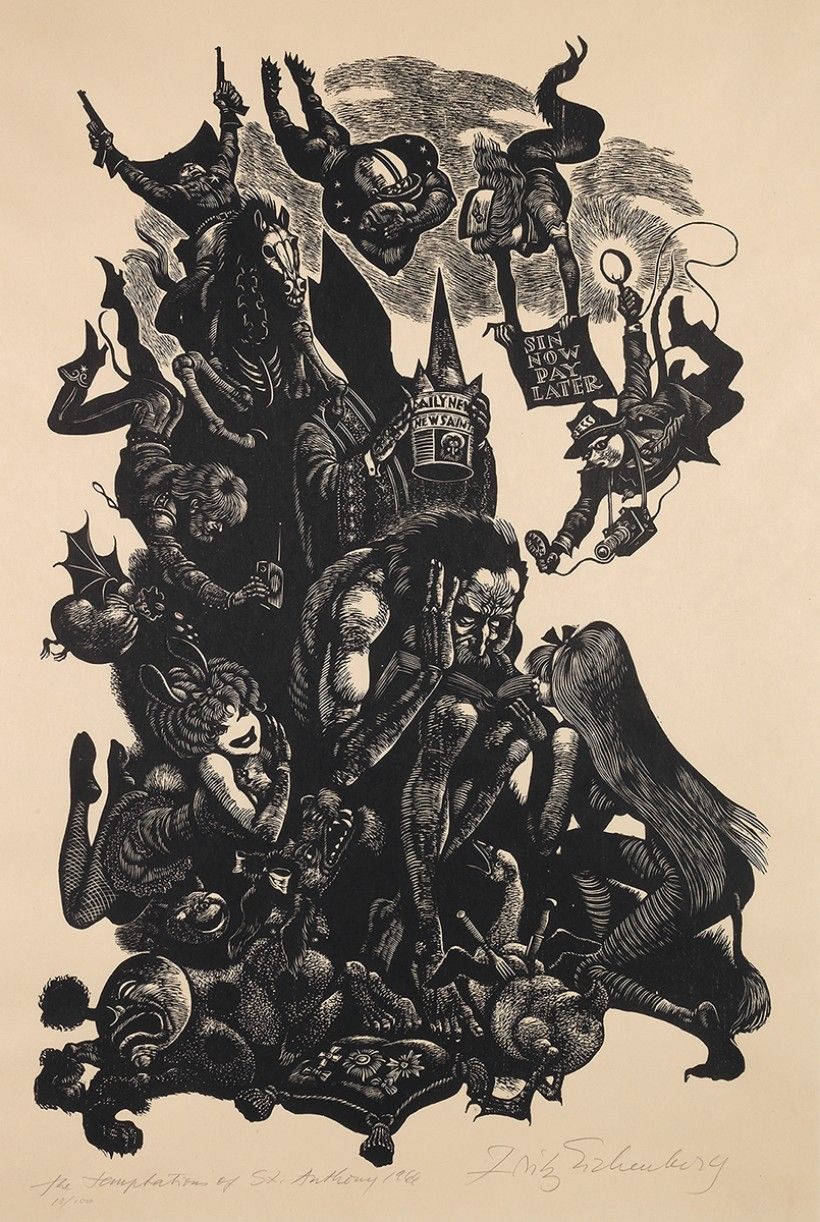

Of all the techniques in Eichenberg’s repertoire, wood engraving was perhaps his most utilized and well-sharpened. Take for instance this piece from the Brandywine's collection, The Temptations of St. Anthony, made in 1966, one out of an edition of 50 reproductions. Anyone who tries it knows that carving into wood can be tricky business; most woodcut favors strong graphic lines and shapes that give room for error and accidental wood chipping. But a glance at this print quickly reveals exceptionally detailed carving and delicate line. How did Eichenberg achieve this? Of course, great skill and many years of practice helped, but a breakdown of a small printmaking distinction shows even more.

As a wood engraving, not a wood cut, The Temptations of St. Anthony could be far more detailed. What’s the difference? Not much! In each technique, the artist carves out everything that we see as white, leaving a “relief” carving of the image (indeed, each is called a “relief” technique in the broader sense”). The area that has been left uncarved gets ink rolled out onto it with a tool called a brayer, and from there the artist can lay paper flat on top and put the “plate” (i.e. the wood carving) and the paper through a press to transfer the ink from the plate to the paper.

The major difference between an engraving and a woodcut has to do with the direction within the carving surface of the wood grain itself. In woodcut, artists use carving knives to cut into the horizontal surface—think classic woodgrain patterns—of the wood piece. In wood engraving, the artist uses a special tool called a burin to cut into what we call the end-grain, which you can imagine as the end of a two-by-four, or what you would see if you cut straight through a tree and looked at the rings inside its trunk. The end grain is a harder, more stable structure which, therefore, allows for far greater detail and thinner carved lines, as seen Eichenberg’s print.

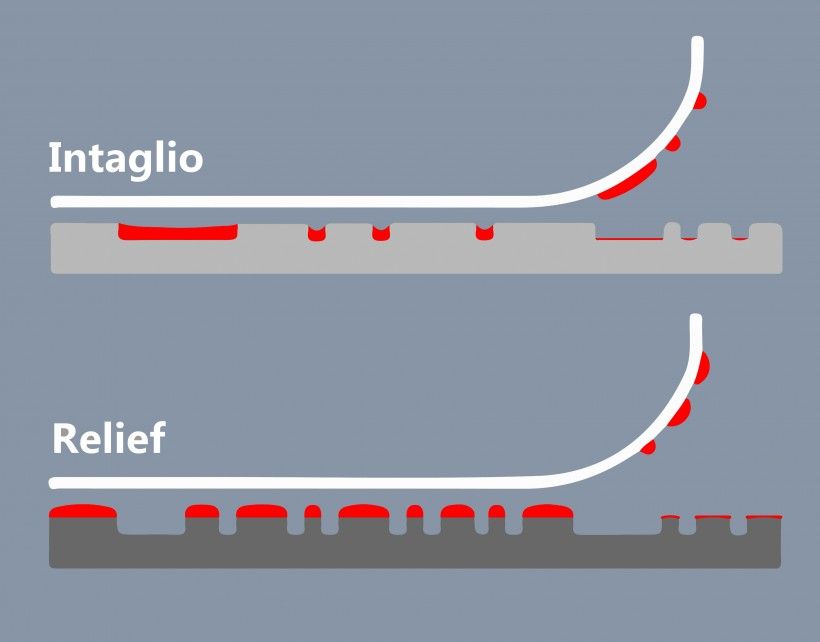

Now traditional metal engraving is in essence the same process of carving also using a burin, but with some key differences. For one, the printmaker carves into a sheet of metal, usually copper, and not wood. Secondly, ink is squeegeed onto the plate instead of rolled, so that the ink sinks down into the carved lines. Next, the printmaker slowly wipes the ink away from the metal surface until the only ink left over is what was pressed into the carved grooves (where it avoids being wiped away). Damp paper is then placed on top of the plate and sent through the printing press, which presses it into the metal grooves, picking up that hiding ink.

Because the print comes from these incised lines, metal engraving is classified as an intaglio print process, as opposed to the relief processes of woodcut and wood engraving. It’s also sometimes referred to as a process by which one draws with black lines on a white background, because the ink directly follows the carved lines. Wood engraving, on the other hand, as a relief method, is a process by which one draws with white lines onto a mostly black background.