Henry Louis Stephens’ Frogs and Other Anthropomorphic Animals

As an intern at the Walter and Leonore Annenberg Research Center of the Brandywine River Museum of Art, I have had the opportunity to process and create a finding aid for the Henry Louis Stephens Collection, which was gifted to the Research Center in 2011 by the collector and Howard Pyle scholar, Paul Preston Davis. The collection contains original drawings, published work and research materials relating to Henry Louis Stephens (1824–1882)—a Philadelphia-born illustrator, cartoonist, author and editor.

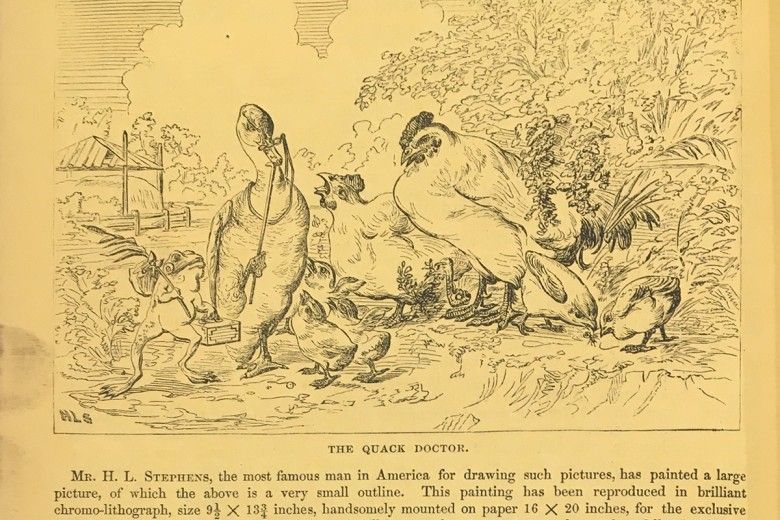

Stephens is best remembered for his book, The Comic Natural History of the Human Race (1851), and an 1863 series of prints about an enslaved man’s journey to freedom. He also produced a significant body of work in periodicals, such as Vanity Fair and Punchinello. Though largely overlooked now, Stephens was highly regarded in his day. For example, an 1868 advertisement in The Riverside Magazine offering a subscription to own a print of the artist’s drawing, “The Quack Doctor,” attests to Stephens as “the most famous man in America for drawing such pictures.”

“The Quack Doctor” exemplifies an aspect of Stephens’ oeuvre that I became especially interested in while working with this collection—the artist’s long-standing interest and highly developed skill in drawing anthropomorphic frogs and other animals.

Examples in the collection show that Stephens’ animals dress and act like humans, to considerable humorous or satirical effect. In the book, A Frog He Would a Wooing Go (1865)—one of Stephens’ better-known works partly due to a 1967 reprint—a frog presented as a pampered, eighteenth-century gentleman attempts to woo Mrs. Mouse at the elegant Mousey Hall, only to be chased out by a gang of cats and ultimately be eaten by a “terrible duck.” Stephens’ illustrations for “Mother Goose’s Melodies”—published as frontispiece illustrations in the first volume of The Riverside Magazine (1867) and later as a book in 1869—constitute another notable example of Stephens’ charming style. One of these depicts a dog trying on a pince-nez, while another portrays a cow in an elaborate frilly dress dancing to bagpipes on a crowded street.

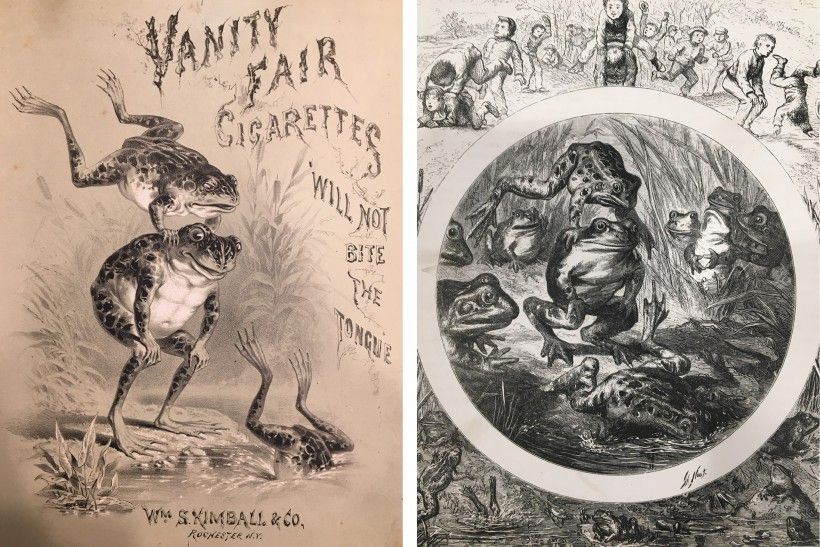

Besides magazines and books, Stephens created numerous anthropomorphic animals for advertisements. However, the published advertisements rarely contain signatures or any other information that would credit Stephens. Fortunately, unlike most artists of his time, Stephens kept examples of his trade-card illustrations and other advertising work in a personal scrapbook, dated 1880 and entitled “Frogs &C.” This rare item, as well as several trade cards that present Stephens’ advertising work, are in the Brandywine Research Center’s Stephens Collection.

The Stephens Collection’s scrapbook contains numerous advertising lithograph print proofs sporting images of frogs and other animals. The variety of situations that Stephens’ animals are placed in speaks to the versatility of his designs, which were used to promote everything from clothes to aromatic schnapps.

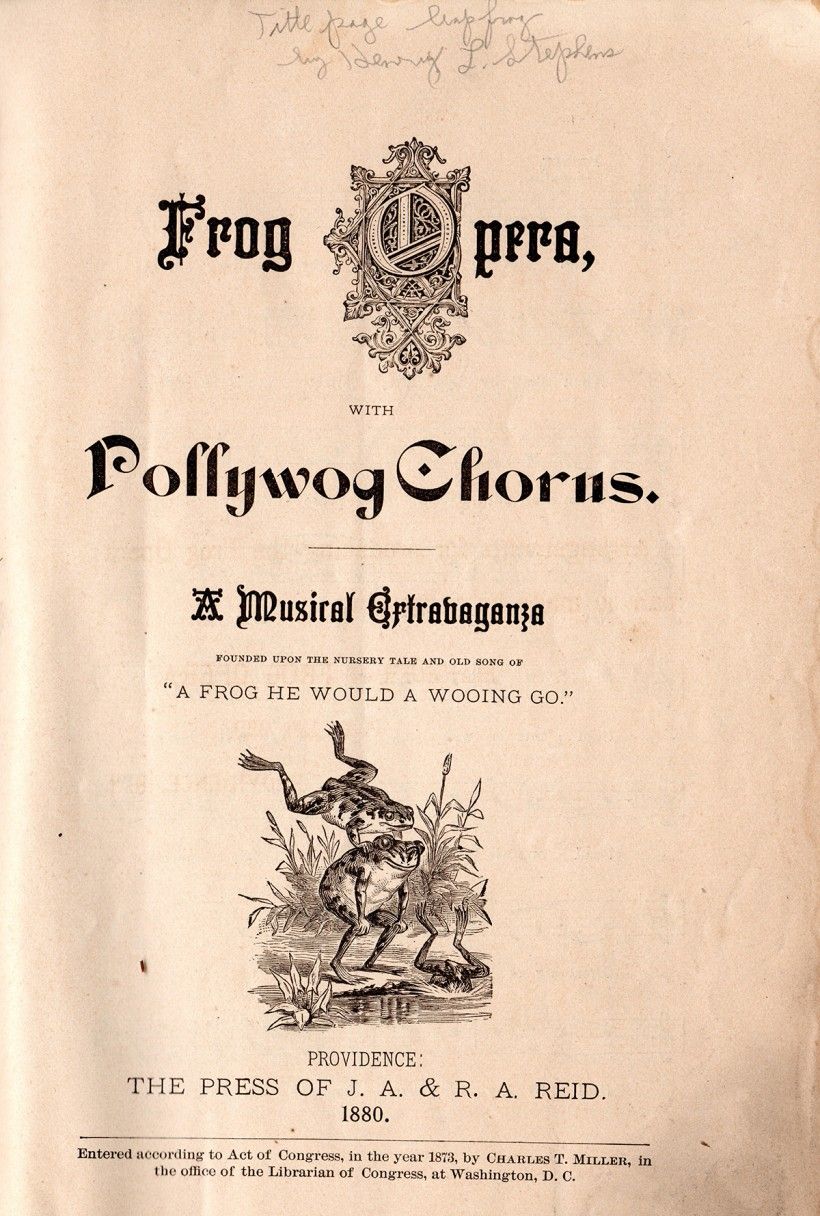

Stephens drew elements of the natural world to cleverly stand in for human creations. Toadstools serve as parasols, flowers as smoking pipes, and cattails as military banners. Several illustrations depict frogs in the game of “leapfrogging.” This was a particularly enduring motif that Stephens repeated with variations in many published works. One particularly notable example of Stephens’ leapfrogging design appears on the title page of the booklet, Frog Opera, with Pollywog Chorus: A Musical Extravaganza Founded Upon the Nursery Tale and Old Song of “A Frog He Would A Wooing Go” (1880).

While looking through the Stephens Collection, I was surprised to also find an 1867 illustration by Thomas Nast in The Riverside Magazine that is quite similar to Stephens’ leapfrogging design. The resemblance suggests that the one artist was influenced by or paid homage to the other; however, while Stephens’ Kimball tobacco advertisement remains undated, we cannot be certain who may have influenced whom.

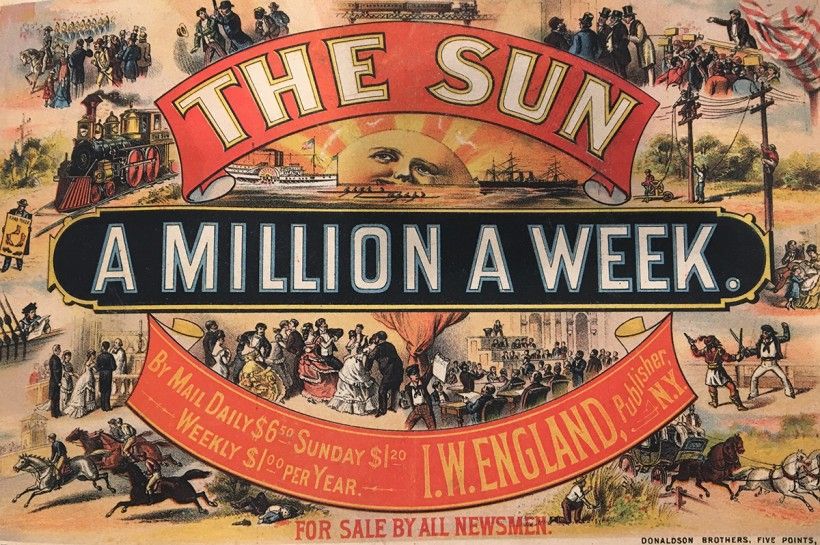

Of course, the works in the Stephens Collection are not limited to anthropomorphic animals. For one, the scrapbook contains several print proofs featuring figures of people in a variety of situations, including an advertisement for The Sun newspaper with scenes including a horse race, a dance party and a duel. Moreover, the Stephens Collection contains four original drawings by Stephens that showcase his skill in drawing political cartoons. Nevertheless, Stephens’ anthropomorphic animals, especially his frogs, are among his most engaging, yet underappreciated, contributions to nineteenth-century American art.

Header Image: Stephens’ illustration, “The Quack Doctor,” in The Riverside Magazine (October 1868).

All archival scans and photographs are from the Henry Louis Stephens Collection, Gift of Paul Preston Davis, 2011, The Walter and Leonore Annenberg Research Center, Brandywine River Museum of Art.