Director's Report

Dear fellow conservationists,

Welcome to the winter edition of Environmental Currents!

This year we’ve been celebrating the 10-year anniversary of the Brandywine Creek Greenway, a partnership that continues to astound me in its scope, as well as the extent to which our partners have continued to work together to make the individual projects of the Greenway an interconnected whole. Over the past decade, much progress has been made so that we can walk, ride, hike and/or float along the many trails of the Greenway, as well as connect with the larger network of The Circuit Trails and share this space with conserved habitat that protects wildlife and natural resources. With much work still to be done, it’s exciting to think of what lies ahead in the next decade and beyond!

In this issue, we highlight Seung Ah Byun, the new Executive Director of the Chester County Water Resources Authority and—of course—former Brandywine Conservancy colleague. With Seung Ah’s expertise and experience, we are sure to see, and look forward to participating in, a wonderful transition from the groundbreaking work done by Jan Bowers from her days at the CCWRA. Best of luck, Seung Ah!

Forests take up a good bit of this newsletter. Staff have been researching various aspects and expertise regarding the forests of southeastern Pennsylvania, and we are still in the mode of exploring how best to conserve—for the long term—this precious and vulnerable resource that is such a critical component of the communities in which we serve.

Also featured in this issue is a Q&A session with our “new” Assistant Directors, Stephanie Armpriester and Grant DeCosta, on their 1-year anniversary serving in these roles as part of the Conservancy’s re-organization, plus a spotlight on our award-winning staff and Art & Nature activities at Penguin Court Preserve.

As we enter this winter season, aside from all of the uncertainty this time brings into our lives, I find myself in awe of the continuing mission of the Brandywine Conservancy. Our work is to preserve land—in perpetuity. The Preserves and spectacular landscapes protected in our 50+ history have been lifting spirits for decades. Lately, the effect of all the accomplishments achieved over the years by Conservancy staff—working hand and hand with you, our partners—in preserving the beauty, wildlife and resources of the lands and waters we call home has been nothing less than life affirming.

We are so thankful that we can be here for you, and we are grateful for your continued support as we forge ahead preserving more precious places, creating more ways for you to enjoy the great outdoors and helping you plan a resilient future.

From all of us at the Brandywine Conservancy, we wish you happy and safe holidays!

Until we meet again,

Ellen

Ellen M. Ferretti

Director, Brandywine Conservancy

Brandywine Creek Greenway Celebrates 10 Years of Accomplishments

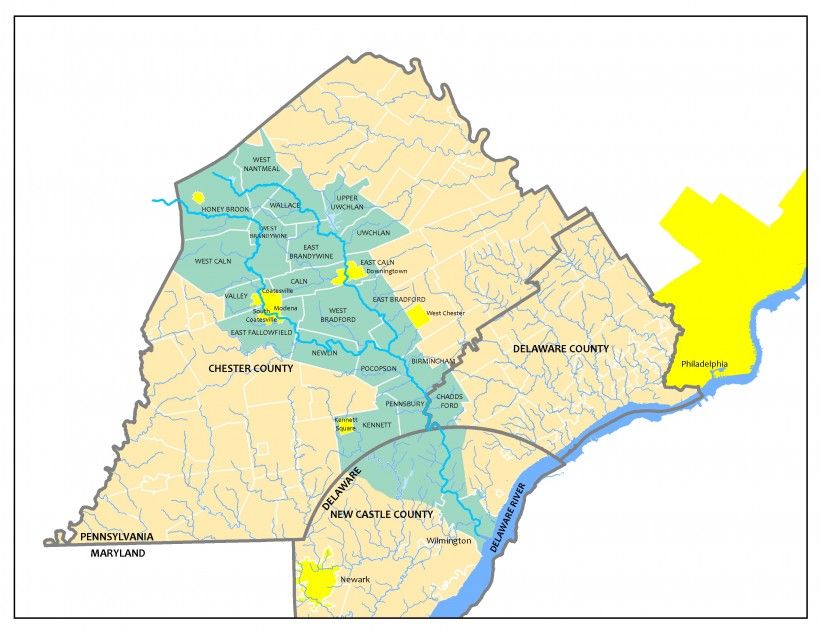

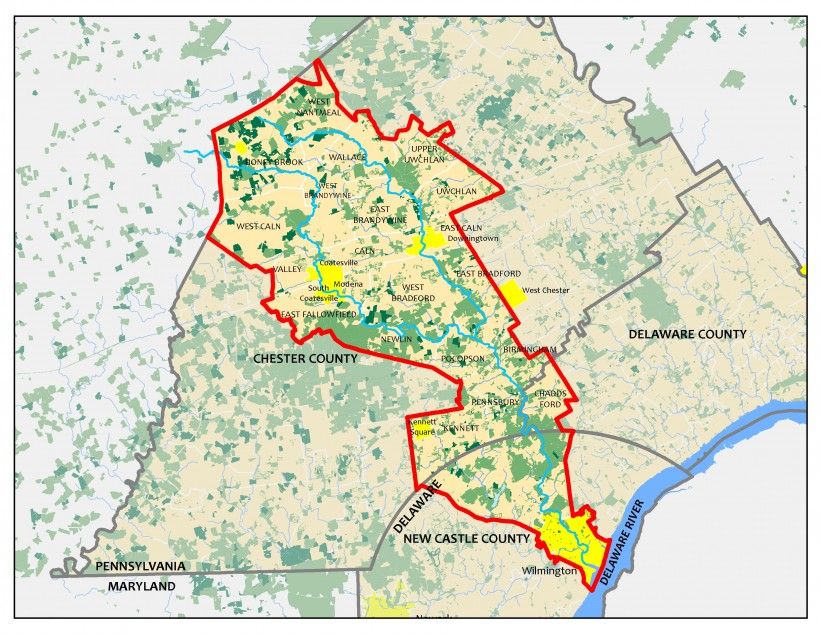

This year the Brandywine Conservancy is celebrating the 10th anniversary of the Brandywine Creek Greenway regional planning initiative. This amazing partnership involves 26 local municipalities, three counties, two states and others that are committed to a common vision for the future of the Brandywine Creek watershed. The Brandywine Creek and its tributaries impact the lives of an estimated 500,000 people who live in its watershed, and it has played an important role in the lives of thousands more who have lived here over hundreds of years.

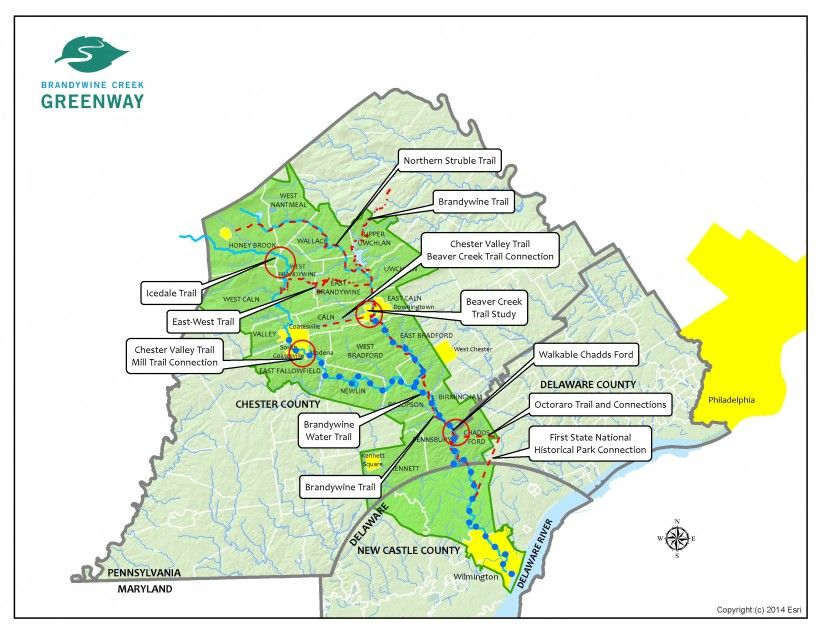

The vision for the Greenway is to create a contiguous conservation corridor of open space and natural areas along the 40-mile length of the Brandywine Creek from Honey Brook, Chester County, Pennsylvania to Wilmington, Delaware, including publicly owned lands that can be accessed through a network of community and regional trails. The Brandywine Creek and surrounding lands are a functioning Greenway today thanks to local municipalities, county and state governments, private landowners and conservation organizations who have successfully protected and conserved many of the Greenway’s resources. Numerous conservation-minded landowners have partnered with private land trusts to protect over 33,000 acres of private land by donating or selling their development rights. Another 8,400 acres of private open space are controlled by Homeowners Associations and permanently protected by deed restriction. Municipal, county and state governments have acquired an impressive 14,000 acres of public open space including the Brandywine Battlefield National Historic Landmark, the First State National Historical Park, three state parks and over 80 municipal parks north of the Delaware state line. The acreage of land permanently protected north and south of the Pennsylvania/Delaware state line totals 55,400 acres in 2020.

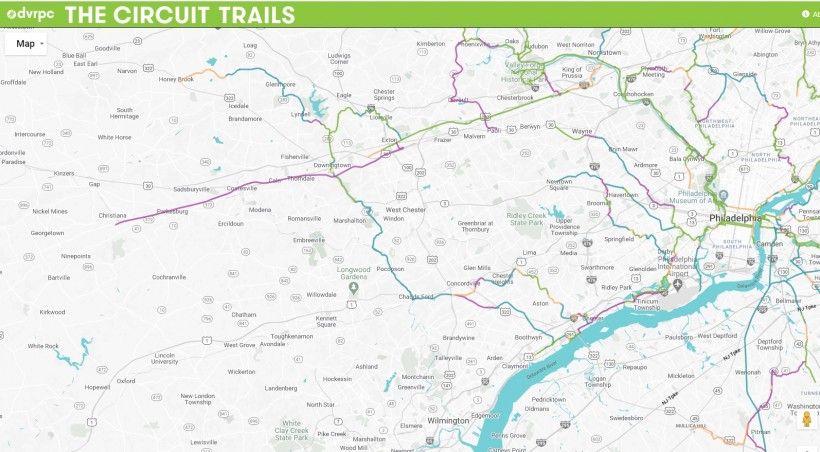

While land and water conservation are the primary motivations for the Greenway, certain municipalities recognize the value in providing public access to protected natural and cultural resources to build a constituency for land and water conservation. Sidewalks, footpaths, multi-use trails, bicycle routes and boat launch areas are important facilities that allow people to connect with their natural environment and can provide unparalleled opportunities for environmental education/appreciation for users of all ages and abilities. Each existing household in the Greenway can save hundreds of dollars each year due to having open space available for recreation and exercise at their doorstep. Three major regional trails in the Circuit Trails network of greater Philadelphia are found within the Brandywine Creek Greenway: the Struble Trail; the Brandywine Trail; and the Chester Valley Trail. Many more community trails (existing and planned) provide important neighborhood connections into the regional trail network.

Since 2014, planners at the Brandywine Conservancy have focused on several important trail planning efforts funded by William Penn Foundation grants for the Greenway. Each trail planning project was part of, or connected to, the Circuit Trails regional trail network of the Greater Philadelphia region.

The Northern Struble Trail Feasibility Study was conducted by Conservancy planners in collaboration with planners at the Chester County Planning Commission. The study examined the potential for a paved multi-use trail along the abandoned Waynesburg Branch of the Pennsylvania Railroad corridor from Marsh Creek State Park to Honey Brook. Once implemented, the northern expansion will expand the existing 2.6-mile Struble Trail by 13.5 miles.

The Brandywine Trail Feasibility Study focused on the route of an existing natural surface footpath along the Brandywine Creek from the existing paved Brandywine Trail near Route 322 in East Bradford Township to a footpath in Brandywine Creek State Park in New Castle County. This 19-mile footpath passes through public and private properties and portions currently are not open to the public.

The Mill Trail Feasibility Study was prepared with the City of Coatesville, South Coatesville Borough and Modena Borough. It explored the concept of a looped trail that connected existing trails, parks and cultural attractions among the three municipalities including a connection to the future Chester Valley Trail in Coatesville.

The Brandywine Creek Water Trail Feasibility Study was completed in close collaboration with 13 municipalities from the City of Coatesville and Downingtown Borough in Chester County to Brandywine Creek State Park in New Castle County. When complete, it will be a 22-mile bi-state recreational water route that connects communities and improves access to the Brandywine for increased water recreational use.

The East-West Trail Feasibility Study was completed in collaboration with East and West Brandywine Townships and Uwchlan Township. The vision was to connect two County facilities, Hibernia Park and the Struble Trail, with a bicycle and pedestrian-friendly trail route of 11.9 miles.

The Beaver Creek Trail Feasibility Study was prepared for Caln Township to study the alignment of a 3-mile multi-modal trail from Caln Park and the Caln Township municipal building to Downingtown Borough with future connections to the Struble Trail.

Two popular Greenway products that continue to complement Conservancy and partner open space and trail planning efforts include the Brandywine Creek Greenway mobile app and the Hiking Through History brochure. Both products encourage residents and visitors to get out and explore all that the Greenway and regional trails have to offer and can be downloaded for free on the Brandywine Creek Greenway’s website.

In addition to Conservancy-led trail planning efforts, several Greenway partners are actively pursuing key trail planning projects that will provide critical links within the Greenway, including: Chester County and the Chester Valley Trail; Upper Uwchlan Township and the Park Road Trail; Chadds Ford Township and Walkable Chadds Ford; East and West Brandywine Townships and Uwchlan Township and the East-West Trail; and East Bradford Township with the Plum Run Greenway.

Looking ahead, generous funding from the William Penn Foundation will allow Conservancy planners to continue to advance several trail planning and implementation efforts across the Greenway through the spring of 2022, including Beaver Creek Trail; PECO Corridor Trail; Concord to First State Trail; Brandywine Creek Water Trail; Mill Trail; and Icedale Trail.

Over the last 10 years, the Conservancy has successfully cultivated municipal, private, corporate and non-profit partnerships; provided technical assistance for open space and trail planning projects; and facilitated new joint planning and implementation ventures in the Brandywine Creek Greenway. While partners were not able to physically gather for our annual Bike the Brandywine event or to celebrate the 10thanniversary in person this year due to Covid-19, the Brandywine decided to celebrate virtually with its “Experience the Brandywine” Photo Contest. Launched in October 2020, the contest had 131 beautiful photos submitted by individuals from across the region. All photograph entries, including four winners, are featured online here. The Conservancy also launched its first round of the Brandywine Creek Greenway Mini-Grant program in November 2020. Funds totaling $40,000 were awarded to seven municipal partners to help them implement park, open space and trail projects within the Greenway.

Grants were awarded to the following municipal partners:

- Chadds Ford Township’s Brandywine Creek Emergency Locator/ Educational Signage Project — $5,000

- East Bradford Township’s Strode's Barn Restoration Design Project — $5,000

- East Fallowfield Township’s Outdoor Exercise ‘Park’ and Park Bench Installation Project — $3,600

- Kennett Area Park Authority’s Project to Convert Former Paved Entrance to Pedestrian Trail — $8,000

- Borough of Modena’s Mode House Park — $9,988

- Pocopson Township’s Restoration of Locust Grove Schoolhouse — $6,000

- Wallace Township’s Burgess Park Rain Garden Restoration Project — $2,400

Since 2010, the William Penn Foundation has invested over $2 millon in the Greenway and that funding has been leveraged to add over $2 million of investment from our municipal partners, the State of Pennsylvania, and many private foundations. The Conservancy is grateful to the William Penn Foundation for generously supporting the Brandywine Creek Greenway regional planning initiative over the last decade and for making it possible for many important partnerships and projects in the Brandywine region to flourish.

The Conservancy congratulates and thanks our Greenway partners for our combined successes and growing partnerships over the last 10 years and looks forward to many more years of partnerships to come.

Q&A with the New Executive Director of the Chester County Water Resources Authority

In the interview below, hear from Seung Ah Byun, the new Executive Director of the Chester County Water Resources Authority, who brings over 20 years of experience to her new role. Prior to Chester County, Seung Ah was a Water Resource Engineer with the Delaware River Basin Commission and the Senior Planner for Water Resources with the Brandywine Conservancy’s Municipal Assistance Program. She has also served as a water resources engineer at CDM Smith, primarily consulting to the City of Philadelphia’s Office of Watersheds and CSO Program.

Seung Ah received her doctorate from the University of Pennsylvania, School of Design’s Department of City and Regional Planning, where she also instructed first-year graduate students through a semester-long workshop focused on neighborhood and municipal planning. She obtained a master’s degree in environmental engineering from Drexel University and a bachelor’s of science in systems engineering from the University of Pennsylvania and is a licensed Professional Engineer.

What are you most excited about in your new position as the Executive Director of Chester County's Water Resources Authority (CCWRA)?

I am looking forward to continuing CCWRA’s missionto provide flood protection, reservoir water supplies, and water science, as well as information and planning to the citizens of Chester County so that they may live in safe, healthy and prosperous communities that sustain the natural quality, quantity and biodiversity of the County's water resources. I am also really excited about being back in Chester County, where preserving the landscape is part of the land and water ethic. I hope to continue the partnerships in which CCWRA has been involved with the municipalities, nonprofit organizations, water users and other government agencies that have worked to protect and restore the County’s valuable water resources.

What are some of your short-term goals for the coming year, and what would you like to focus on in the long-term?

For the coming year, I plan to continue to learn about managing CCWRA’s four dams and the various projects related to flood protection, stormwater management, water quality, and education and outreach in which we are involved. Over the next couple years, we are focusing on updating the County’s water resources comprehensive plan, Watersheds, the County-wide Act 167 Stormwater Management Plan, and an updated Stormwater Management Ordinance by the end of 2022. In the long-term…can you ask me that again in a year?!?!

How do you see your goals building upon the previous efforts of the CCWRA to move the needle of success further?

First, it’s going to take some time for me to wrap my head around 24 years of work that Jan Bowers had led with CCWRA. I think tapping into the changing and diverse population in Chester County will be key to furthering the success of our previous efforts.

With your varied background, you bring so much great experience and perspective to your new position. Can you tell us a bit more about your past experience and how you think it will aid you in your new role at the CCWRA?

I hope that I can bring some different perspectives and experience to CCWRA and the County. Most recently, working at DRBC offered experience not just as a regulator, but understanding how to plan at the Basin-wide, multi-state scale. I’ve also studied multi-state initiatives when I was working on my dissertation evaluating state programs for nonpoint source pollution (e.g. stormwater and agricultural runoff) in the Chesapeake Bay watershed. I really enjoyed my time working for Brandywine Conservancy. It was my first real experience with a non-profit. At the time, I was able to take part in the partnerships that the Conservancy developed with other nonprofits, private partners and government agencies. Over my 20+ years in the water resources field, I have been fortunate and grateful to have had managers who taught me not just knowledge of water resources and conservation, but also how to be a good leader. I like to believe that my experience will help me continue CCWRA’s great work to manage the County’s water resources.

Is there anything else you would like to tell us or share?

Once we move past the COVID pandemic, I am really looking forward to getting back to two of my favorite Brandywine Conservancy events, the Radnor Hunt Races and Tip-a-Canoe.

Understanding Your Woodlands: An Important Classification Tool for Municipalities

Prior to European colonization, much of Pennsylvania was continuously wooded for millennia, making woodlands the defining habitat type of our area. Local wildlife and natural ecological systems evolved under these heavily forested conditions. However, since settlement, these woodlands have been dramatically reduced through agricultural production and urban and suburban development. Further development, as well as disease, pests and climate change, continue to threaten the woodlands that remain.

Woodlands provide a variety of important environmental, social and economic values and functions for our communities here in southeast Pennsylvania. Trees reduce and slow the impact of flood waters by absorbing water through their roots and infiltrating precipitation as it falls. On steep slopes or along streams, trees help reduce erosion, while their shade, root systems, and addition of leaf litter to waterways can have beneficial water quality impacts that protect valuable in-stream habitat for aquatic insects and fish communities, as well as drinking water that may be extracted further downstream. Woodlands also provide critical sources of nectar, pollen and habitat for our critical pollinator communities during the various stages of their life cycles. In addition, woodlands provide natural barriers and filters for both sound and air pollution, while simultaneously acting as the lungs of our planet and living organisms that actively perform carbon sequestration services, reducing the impacts of climate change. Indeed, the recently published Return on Environment report estimates that on our protected lands alone, trees store a tremendous amount of carbon in Chester County that would cost $120 million to replicate.

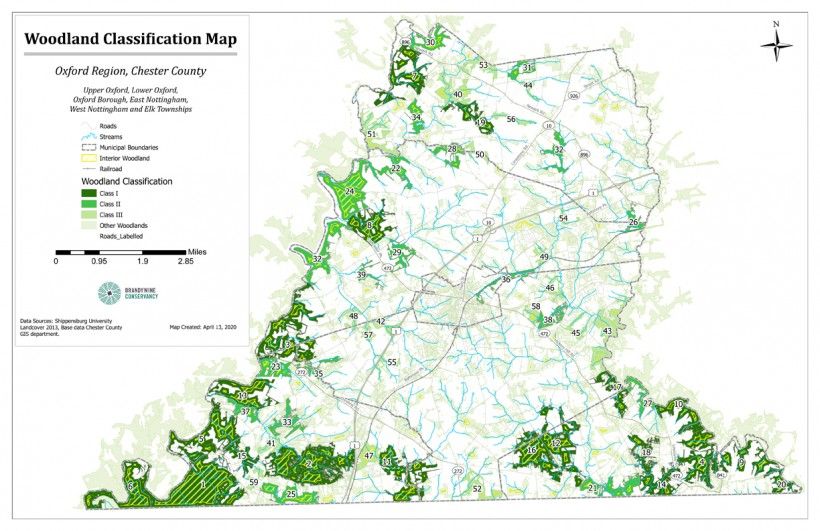

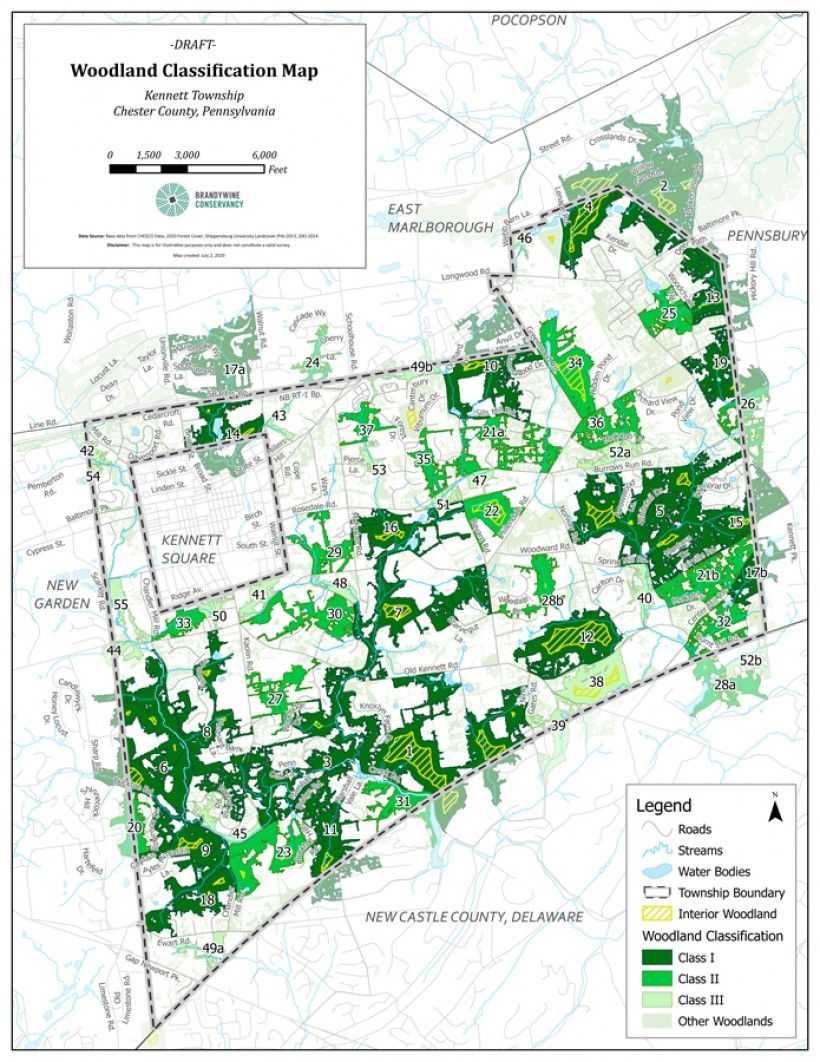

Many municipalities recognize the importance of our remaining woodlands and provide for their protection from development through a variety of provisions set forth in their municipal Zoning or Subdivision and Land Development Ordinances. A selection of municipalities have also taken advantage of a Geographic Information systems (GIS) based Woodland Classification Tool developed by the Brandywine Conservancy’s Municipal Assistance Program to further understand the relative importance of the woodland contained within their municipalities.

Given that woodlands vary in size and perform varying functions across the landscape—depending upon how they are located in relation to other resources and sensitive areas—they can be prioritized and grouped into different classes.

Utilizing GIS and a high resolution dataset of woodlands obtained through remote sensing technology, the Brandywine Conservancy evaluates woodlands based on their overall size, the presence and size of any interior woodlands (those areas of woodland buffered by an additional 300’ of woodland), the presence of streams that they protect, and whether the woodlands align with steep slopes or headwater areas within the municipality. These characteristics are quantified, and woodlands are then ranked against one another into three separate classes, with Class I being the most important from a functional perspective. These woodland classes are then mapped and also evaluated against protected lands within the municipality, drawing attention to those woodland patches that rank highly but are not yet permanently protected. Typically, those woodland patches of greater size will rank higher as they tend to provide the most benefits or services.

Recently, the Brandywine Conservancy has assisted the Oxford Region Planning Commission (East Nottingham, Elk, Lower Oxford, Oxford, Upper Oxford and West Nottingham) and Kennett Township in conducting Woodland Classification projects to help evaluate the comparative importance of their woodlands and the benefits they provide for water quality, critical habitat and community well being. If your municipality is interested in conducting a similar woodland classification mapping exercise and potentially aligning it with improved resource protection provisions in your Zoning Ordinance, please contact Grant DeCosta, Assistant Director for Community Services, at [email protected].

Q&A Session with the Brandywine’s New Assistant Directors

Last year the Brandywine’s Stephanie Armpriester and Grant DeCosta were promoted to new Assistant Director roles as part of the Conservancy’s re-organization. Stephanie was promoted to Assistant Director for Conservation, where she is responsible for the Conservancy’s work in Easement Stewardship and Land Conservation, and Grant was promoted to Assistant Director for Community Services, where he is responsible for the Conservancy’s work in Municipal Assistance and an expanded effort toward offering additional Land Stewardship services to our partners in conservation. In the below Q&A session, Stephanie and Grant reflect on their one-year anniversary in these new roles and their goals moving forward.

Both of you bring a wealth of experience and expertise to your new roles. Can you share a little about your backgrounds?

Stephanie: I’ve been working in the historic preservation planning and land conservation fields for over 10 years. For me, my career path began with an interest in historic preservation. Through my graduate studies at Cornell, I realized that preserving the built environment was only a small piece of the puzzle after taking courses in Landscape Architecture and a special course about preserving the agricultural landscape. This hit home for me as I grew up in Southern New Jersey and witnessed multi-generational family produce farms being transformed into residential housing developments, creating increased traffic and high property taxes. I also spent several years working in farmland preservation in Lancaster County, working mostly with Amish farmers, where I saw the opposite value—preserving productive farmland as the #1 priority while planning for smarter growth strategies in designated areas. I saw firsthand how land conservation was a key way to boost the county’s biggest industry—agriculture—and provide opportunities for better farmland access and affordability to younger generations.

Grant: Prior to my current role, I enjoyed over six years in the Conservancy’s Land Conservation Department. I initially learned of and was drawn to the Conservancy from my five-year tenure at Chester County’s Department of Open Space Preservation. In that experience I was fortunate to work with every conservation organization and municipality in Chester County that had received funding from the County’s now 32-year open space preservation programs. That interaction gave me the opportunity to learn from the good work of all in this field. This is incomparable from other areas I have lived and worked including Annapolis (MD), Virginia and Florida. Following my studies at Virginia Tech, I have worked in various natural resource careers and feel those experiences gave a me holistic lenses to view what has been accomplished here, especially as my family makes our home on my wife’s parents’ property protected via a Brandywine conservation easement.

Tell us more about your new roles, how you transitioned into them and what your goals are moving forward.

Stephanie: In my new role I oversee the Land Conservation and Easement Stewardship departments. I have a wonderful team that’s top notch in the field. We are continually learning as we challenge each other to think from different perspectives. As we look to the future, we are focusing on streamlining our easement processes, cross training our staff, and boosting our proactive approach to our easement landowners. Through our new Community Services program, we are building ways to provide technical assistance and grant funding to our easement landowners to help them manage their natural resources on their eased property. Our biggest change during my first year in this role has been transitioning to the WeConservePA model easement, which will allow us to adapt our approaches to our easements in line with other land trusts in the Commonwealth, including working with our peers in interpreting and enforcing the same easement language consistently.

Grant: I am leading the newly created Community Services department Stephanie referenced. It is a result of merging the Municipal Assistance Program with our land restoration work and municipal stormwater assistance. Working more inline with our team of talented municipal planners has been a rewarding experience. My breadth of experience across the organization helps me appreciate the talent this organization has long secured and cultivated. I hope to provide steady continuity to the pioneering work the municipal assistance program has provided almost since the Brandywine’s founding 53 years ago while supporting opportunities for innovation by staff. They are not waiting for me to provide those opportunities, so I enjoy the pressure to keep pace with their ideas needing funding. The introduction of the Community Services component to our programming melds this work and provides for flexibility in expanding our programs and recognizing a key expansion of existing programs that benefit more of our stakeholders.

Stephanie, how did the Land Conservation and Easement Stewardship teams’ work adapt during COVID?

Stephanie: Along with all at the Conservancy, my team worked hard to transition to remote work as seamlessly as possible. We found creative ways to do our traditional work remotely while still advancing projects and meeting our monitoring goals for the year. This included identifying an aerial image service, NearMap, for remote monitoring. We hold the second highest number of conservation easements in the Commonwealth so finding ways to meet our monitoring obligations was very important. We have done 70% of our monitoring this year using NearMap and it has been a huge success. In addition, a staff person was trained to be able to do notarizations remotely to continue document execution with stay-at-home orders in place and also officially transitioned to e-Recording for all of our documents. As they say, necessity is the mother of invention! We are adopting all of these changes permanently in some form moving forward as we have shifted the way we think about how and where we work.

Grant, what type of innovative projects have your staff been working on lately?

Grant: Much as Stephanie is able to celebrate the new model easement, we are seeing innovation ongoing. On the Brandywine Creek Greenway front, we’ve expanded into Delaware, introduced a new Greenway mini-grant program, and completed a feasibility study for a Brandywine Creek Water Trail (the first potential water trail in southeastern Pennsylvania). Other recent work includes the completion of new municipal natural resource protection ordinances; increased use of our Sustainable Community Assessment; securing new funders (including Delaware funders investing in Pennsylvania to secure their drinking water source); providing municipalities assistance with their stormwater management obligations, including assisting with the implementation of cost-saving Green Stormwater Infrastructure (GSI) practices; and recognizing our long-established techniques that yield success in—and opportunities to increase—both the adaption and mitigation of strategies that increase climate resilience.

What aspirations do you both have for the future of the Conservancy and this ongoing work?

Stephanie: We are in an opportunity zone where conservation easements can play a key role in our biggest generational challenges, including farm and food access and affordability and climate change. We also have a wide array of constituents, visitors, supporters and landowners, who are eager to be a part of the solution. We are uniquely positioned to address these challenges head on by bringing together our diverse stakeholders to educate, plan and implement at the local level to preserve our natural and cultural resources for generations to come.

Grant: I feel very fortunate to see a continued desire for our services and our ability to respond in-kind. The Conservancy made key strategic investments in technology just prior to the onset of COVID restrictions that enabled our staff to seamlessly embrace the transition to remote work. The public appreciation for our long legacy of work in the region continues to reinvigorate me during this challenging time. There will always be challenges to success in this field: more funding is always needed, developers seek similar properties that we feel are inappropriate for development, elected officials transition, and we lose keystone properties, but we persevere aided by the strength of our supporters. We thank them all as we strive to conserve our natural resources, sustain communities, and protect cultural resources for all present and future generations.

I like to imagine this is the world the Conservancy was formed under as our founders took a stand against unregulated development encroaching into this effortlessly artistic landscape that fueled the industry of a nation, provided refuge to those escaping a nation torn from within, and needing to define the limits of the seemingly unstoppable D.C. to Boston megalopolis. They succeeded so it is an easy and honorable mantle to upload. My coworkers provide me the comfort that as an organization we are prepared for the challenge. I enjoy the pressure to work as hard as they do to secure the future of my chosen home.

Invasive Species Spotlight: Japanese Pachysandra (Pachysandra terminalis)

Japanese pachysandra is a popular landscaping plant chosen by homeowners as a ground cover for hard-to-grow, shaded areas and areas with poor soils. The problem? This plant has no boundaries and doesn’t know when to stop. Pachysandra terminalis is a hardy perennial that spreads to form dense mats of groundcover. Japanese pachysandra can quickly overrun the intended garden boundaries, escaping into the natural landscape and outcompeting native plants.

Click here to learn more.

“Paint Out” at Penguin Court

At the end of September 2020, the Brandywine’s Penguin Court Preserve hosted 14 artists who were participating in the Southern Alleghenies Museum of Art’s 12th annual “Paint Out.” Artists were encouraged to visit public spaces and special places, with permission, and create art in the plein air method. Their resulting art was later exhibited and sold at the Museum’s Ligonier location.

Painting en plein air—the act of painting outdoors—can present challenges for artists, from bugs to inclement weather. Besides precipitation causing obvious difficulties, dampness may lengthen the time needed for paints to dry and it could make drawing harder. On the other hand, warm and sunny conditions may cause paints to dry and harden too fast, making them unusable.

This was the first time artists were welcomed to Penguin Court, and visitors were taken aback with the beauty of the preserve.

Melissa Reckner, Penguin Court Program Manager, said she enjoyed seeing what scenes from across the property captured artists’ attention and then checking in to see how the viewscapes were captured on canvas. “I thought it funny that artists nearly equally spaced out across the property, with three artists working by the pond, four at the old mansion site, and three at the conservatory when I made a round to check in on folks.”

Reckner was thrilled to see that the first and second place pieces were of scenes painted at Penguin Court. Marcia Koynok won “Best of Show” for her oil canvas depicting fog rising from the Ligonier Valley beyond a field of goldenrod, and Patricia Young won the “Award of Excellence” for her pastel piece showing the westward scene of Chestnut Ridge with that morning fog in the valley.

The Southern Alleghenies Museum of Art (SAMA) Ligonier Site Education Coordinator, Kristin Miller, stated that this is one of her favorite events of the year. “This event is exhilarating for SAMA and the community. This all-weekend affair gives visitors and artists alike, the opportunity to view and purchase artwork, created over three days, capturing the beauty of our historic valley. This Plein Air “Paint Out” is the first of its kind in the area. It truly promotes the arts and enhances tourism in the community, encouraging guests and artists to explore Ligonier to see what our lovely town has to offer.”

Miller added that “the SAMA Paint Out has grown over the last few years and we have seen our participating artists double in numbers. The artists really enjoy the weekend and look forward to it each year. We try to make them feel at home and let them know that they are truly appreciated for what they do. SAMA and the artists are so very thankful for having the opportunity to paint out at Penguin Court this year! It was an absolute honor, and the artists could not stop talking about its beauty and grandeur.”

Penguin Court and SAMA hosted a “Monarchs, Milkweed and More” program for the last two years, with 2020’s event being held virtually due to the pandemic. The groups look forward to working together more in the future.

Brandywine's Award-Winning Staff

Congrats to the Brandywine Conservancy’s associate director, John Theilacker, and Penguin Court program manager, Melissa Reckner, on their recent awards!

John received the Pennsylvania Chapter of the American Planning Association’s (APA) esteemed “Award for a Leader — Professional Planner,” and Melissa received this year’s “Woman of the Watershed” award at the 2020 Women In Conservation Awards hosted by PennFuture. You can read more about their awards here and here.

Header photo of the Brandywine's Laurels Preserve by Chuck Bowers.